Screening & conversation with Lee Kai Chung

Artists in Conversation between Lee Kai Chung and Yuhang Zhang

October 08, 2022

Close-up cinema | London

Yuhang Zhang (Y): Thank you Chung for the screening session.

Can you tell us briefly about the contexts of

the three films?

Lee Kai Chung (C): I'm interested in the history of social movement and how archive can contribute to the social narrative. That's why I came up with the first film (Can’t live without, 2017). During my artist residency in Seoul, I did some research in the archive of Soeul’s MMCA (Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art). I realised that, emotions of people and the essence of human will not be fully demonstrated or shown in those archival materials, especially when the material is kept in an underground vault, away from the public. You can hardly get access to the archive, just like the remains of human are buried underground.

That's why I emphasise quite a lot the emotions of those people. For the second film (The Retrieval, Restoration and Predicament, 2018) - I will consider that being the first project of my longer series call Displacement. Displacement is a very tricky concept in the context of Chinese or Cantonese. When we put it in English, it’s not straightforward, but at least we know what it's about. But when we translate it into Chinese, we can't just put it as “leaving from one place to another”. There’s something beyond that. During my film research or interviews, people who travel from one place to the other feel like belonging to a particular place. That place does not necessary need to be their home nor a place at the present, it could be somewhere in the past or in the future, or even somewhere that doesn't exist at all. This kind of mental displacement has always been a focus in the creation of my work.

Image still, The Retrieval, Restoration and Predicament, 2018, single-channel video

The film is about the public statues in Hong Kong, particularly

the statues set by the royal family of Britain when they occupied Hong Kong as a

colony. They erected a lot of statues of similar kinds in Hong Kong. During the

World War II, the Japanese army confiscated

those statues and brought them back to Japan. They melted them and remade them

into weapons, using them to invade other southeast Asian countries for the "Greater

Asia”. But after the war, the

British Hong Kong Government retrieved four of the statues. Therefore

the film is about the whole process of retrieving those statues, repairing

them and representing them again in the colony and reflecting what I call the “icon

of a colony”. No

matter if it’s in the past, in the archives, or in the present when I was

creating that work.

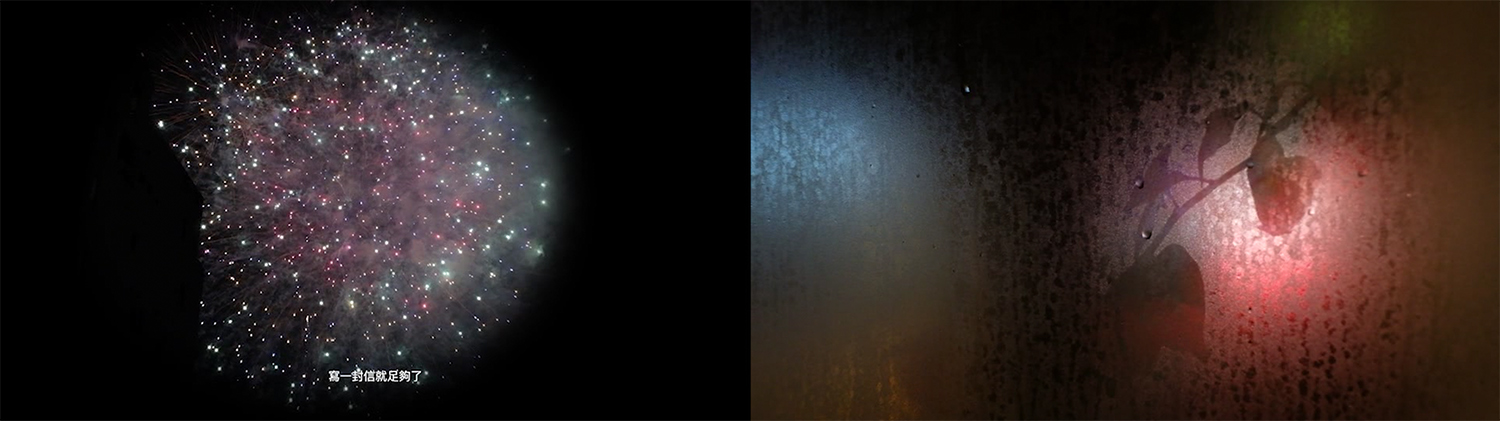

Image still, The Remains of the Night, 2020, double-channel video

The third film (The Remains of the Night, 2020) is my

second series in the Displacement project, called Narrow Road to the

Deep Sea. It is particularly about bacteriological and biological warfare

in South China in Guangzhou.

We all know about the Japanese biological units 731 in Dongbei, Harbin. But then

there was also another unit in Guangzhou. The film depicts a love story between

a couple met in the refugee camp in Guangzhou. It’s about a Hong Kong person

being expelled from Hong Kong to Guangzhou, stayed in the refugee and met a

girl in that camp. This is pretty much about the context and the relationship

between the three films.

Y: Thank you Chung for sharing the contexts. You just mentioned that your practice and research is very much archive-based. In many cases in your work, you bring a broad characters or agencies towards the narrative.For example,in the second film The Retrieval, Restoration and Predicament, the statues tell their own story during the World War II. Could you tell us more about this method of putting characters or agencies in a more or less fictional way, and why you choose to address your archive in practicing this way of representation?

C:

This is a very crucial poing about my practice.

In my early career,

I always told people that I am an artist who works with

archival material or

archives. However, for most of the time, archival material is not always

available. Sometimes when I research certain kinds of issues, I can't get

assess to them due to my identity.

Not being able to see those materials is a very common

situation in my practice.

On the other hand,

no matter in Hong Kong or in UK, I realise that the essence of human does not

really exist in the archives. Those materials are always about the conversations

between officers who

would rephrase the conversation in a very mechanical way in order to clearly inform

what's going on between two parties. I want to insert more about the human

emotions, which, in

my personal opinion, is ignored in those materials. That's why when I read through those

materials, I

always have a word in my head like “How can I interpret this person” or “What

is the background of that person

and what is his accent or his intention of saying that phrase?” Thus,

I like putting those films or particularly essay films in a very humanistic,

narrative way or a speculative manner.

Y: You mentioned those characters or human beings in your film, but those ghosts or hauntological things are also kind of a theme in your work, right?Could you tell us more about these ghostly beings in your work?How do they relate to your engagement with archival spaces?

Image still, Can’t live without, 2017, single-channel video

C:

What you said is referring to particularly the first film Can’t

Live Without where one of the two female protagonists is a ghost, not a

human figure. Telling stories through the mouth of a phantom or a ghost is my

personal interest. I like going to the cemetery to hang out ever

since I was very little. And sometimes I see things, but

that's not completely relevant.

When I was doing my research in Manchuria, I went to Boketu

Railway Station with my wife. It is one of the major railway stations near northwest Manchuria and is very close to inner

Mongolia. It was a large railway station back in the Manchukuo era as well. By that time it was occupied

by Russian, Japanese and the particularly by the communist Chinese government

after the establishment of PRC. But the whole town remained in what it

looked like in the 1980s. The time is frozen. People there were gone. Some places

were turned into desert.

We went up to a very clean, open wide green slope, which is

pretty much like the wallpaper of window 95. I told my wife there was very nice

view to hang out but she didn't want to, so I went there by myself. After walking for about 10 meters,

I realised I was surrounded by skeletons - it was a cemetery. It looked like local

people just wanted to dig down the ground and to build something. But for some

reasons they just left the remains of the dead there.

I’m not looking for ghosts or

phantoms, or the people from the past. But they're looking for us, or, as you referred,

in the form of hauntology. I believe we are not evolving from the

past in a linear way. The past always comes back to the present over

and over again, just like a cycle. The future is sometimescancelling itself.

This concept influences my work a lot: my work is a lot about dealing with issues from the past, and

how I represent them in the present.

Y: Going through your films, a sense of being jammed or in prison is revolving systematically in your works. For example, doing full-time labour in the state of imprisonment in a desperate or even fatal situation, or the monologuing male and female refugee in The Remains of the Night. Could you tell us more about this sense of being incarcerated, imprisoned, or being haunted

C:

It relates to what I experienced

in Hong Kong, I can tell a little bit about my experience. The last work is a

double channel video. When I was creating that work, it was 2019. I was in an

artist residency in Japan. One night, I walked along on the streets, I made a

turn at a corner and saw huge fireworks. I was curious why everyone was wearing

kimono. I then realised that it was the summer festival. It is a huge festival

for the Japanese people. At the same time, tear gas was thrown in Hong Kong in

June 2019. I flew back to Hong Kong a few days later. I experienced, instead of

firework, tear gas. That's why there are lots of smoke and gas and irritation

on the eyes in the film. That's my personal experience.

That is like a collective trauma, I’m just one of the people who lived in Hong

Kong no matter is before or after the social movements, and how we treat our

own identity and how we get over it and evolve into something else. Especially,

the last work was finished right before the outbreak of pandemic in Hong Kong.

Afterwards, I realised that, you're in complete confinement. You cannot travel

as we did in the past.

![]()

![]()

C:

It relates to what I experienced

in Hong Kong, I can tell a little bit about my experience. The last work is a

double channel video. When I was creating that work, it was 2019. I was in an

artist residency in Japan. One night, I walked along on the streets, I made a

turn at a corner and saw huge fireworks. I was curious why everyone was wearing

kimono. I then realised that it was the summer festival. It is a huge festival

for the Japanese people. At the same time, tear gas was thrown in Hong Kong in

June 2019. I flew back to Hong Kong a few days later. I experienced, instead of

firework, tear gas. That's why there are lots of smoke and gas and irritation

on the eyes in the film. That's my personal experience.

That is like a collective trauma, I’m just one of the people who lived in Hong

Kong no matter is before or after the social movements, and how we treat our

own identity and how we get over it and evolve into something else. Especially,

the last work was finished right before the outbreak of pandemic in Hong Kong.

Afterwards, I realised that, you're in complete confinement. You cannot travel

as we did in the past.

![]()

![]()

Installation view, “Late Port”, Lee Kai Chung, Tabula Rasa Gallery (London), 2022

I didn't realise this underlying

sense of confinement in my mind until “Late Port”, this exhibition in which we put together

various works of mine from different series. In my recent experience of having

my work in shows, most of the curators will put my work in a series, series

A,B,C in one exhibition. But in this exhibition or in this screening programme,

I tried to interweave these different works from different series together. In

doing this, we feel the sense of imprisonment.

I didn't realise this underlying

sense of confinement in my mind until “Late Port”, this exhibition in which we put together

various works of mine from different series. In my recent experience of having

my work in shows, most of the curators will put my work in a series, series

A,B,C in one exhibition. But in this exhibition or in this screening programme,

I tried to interweave these different works from different series together. In

doing this, we feel the sense of imprisonment.

Y: Thank you, and a final quick question regarding the body and physicality. The bodily suffering is an important aspect of your works. In the third film for example, there was almost a cruelty about the body being punished, being butchered with a sort of indifferent or detached manner. In the same time, you also like to show your body, for example, your heavily tattooed hands appear every time in your work. I was wondering why you chose to represent the body/physicality in such a special way?

C:

I can tell a very

technical process of how I made my work. I always have my

own archives whenever I come up with a film or a video work or a video installation, I tried to take video from my own archive - the video I took in the past, no matter they are

taken in digital film or 16mm. I would film for commissioned work, but that is

not very common in my earlier work. For The Shadow Lands

Yonder, the work in the gallery is a commission. So I filmed the whole

film particularly for the project. That's why sometimes when I wrote my

scripts, I realized that, I have that film

that I filmed a several years ago. With these, I wrote a newer line, referring to that clip and that is like a working process for me. Going back to the archive

and coming up with a new idea. Then I try to interweave

both the text and the visuals together. Sometimes I film my own hands and then come up with a new idea.

Pain, torture, and emotion are also my personal

experience. I have a lot of tattoos. Many of you may have that experience. The sense of damage and renewal in your body. You recovered, built new flesh, you

become a new self. However, tattoo is like

constantly damaging your body. Tattoo artists will try to limit one session to around one hour or,

1.5 hour. The human body, the sense of pain, this kind of feeling is

sent from the nerve. It is sent from your body to warn you that you are being damaged. So you have to learn to be fine with what is happening to your

body.

As this is a process that you are constantly being damaged, at some point, your body will generate something to compensate that pain. Then up to a certain point,

you will have ecstasy. You will feel high because human body cannot feel being damage or suffering

from pain for a very long time. You will pass out or you cannot take it.

That ecstasy will

last for like 5 to 10 minutes.

Chen Jieren(陈界仁) , a very renowned Taiwanese video artist, has a work about an execution method in ancient China: torture to death (凌迟). The executioner will cut the criminal a thousand times, cutting the flesh from the body, until a few days later, when the prisoner die of losing

blood. But before that, the executor will give him some

opium.

Chen Jian Ren decides to make use of some film photographs taken by a French photographer. The photography are about the criminal who is photographed with a smile when he suffered from the pain. I read a little bit about the work. The depiction of this ecstasy not only aims to blur the line between if the criminal is

having ecstasy or he's happy or he suffer too much. Furthermore, it explores the dignity of being a photographer. The relationship between the photographer and the photographed is highly hierarchical - the photographer captured the moment of torture, representing the suffering of the death row prisoner from a foreign gaze, but we would never truly know the prisoner's embodiment.

ABOUT the Speakers

Lee Kai Chung (b.1985, British Hong Kong) is an artist based in Hong Kong. Lee is pursuing a Ph.D. program in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He performs artistic research on historiography, ideology, and time-transcendence of emotion. From his early explorations of archival systems for historiography, Lee has developed an archival methodology that extends to research-based creative practices - including publishing, spatial production, public engagement, and the archives-making. Through performance, moving images, installation and publication, Lee considers the individual gesture as a form of political and artistic transgression, which resonates with existing narratives of history. In 2017, Lee initiated a hexalogy of consecutive projects under the theme of Displacement – to take a departure from the socio-historical implication under the Pan-Asia context, the series examines human conditions and their geopolitical relations arising from dispersion and material flows.

In 2022, Lee is awarded The Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography from Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University, and he received Altius Fellowship from Asian Cultural Council in 2020, the annual Award for Young Artist (Visual Arts) from Hong Kong Arts Development Council and WMA commission Award from WYNG Foundation in 2018.

His recent and upcoming exhibitions include ‘Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present’ (2023), ‘Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur’ (2021) (Winterthur, Switzerland), ‘Seoul Mediacity Biennale 2018’ (Seoul Museum of Art: Seoul, South Korea), ‘12th Shanghai Biennale: Proregress – Art in an Age of Historical Ambivalence’ (2018) (Power Station of Art: Shanghai, China) and ‘Artist Making Movement - Asian Art Biennial 2015’ (2015) (National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts: Taichung, Taiwan). His work The Retrieval, Restoration and Predicament is in the permanent collection of the M+ Museum.

https://www.leekaichung.com/

Yuhang Zhang is a writer and researcher based in London and Guangzhou. Yuhang is currently a PhD student in Goldsmiths, University of London as The Asymmetry PhD Scholarship Scholar. His research and fiction writing centres around theory-fiction and occulture, looking into urban infrastructures and media landscapes in Posthuman Gothic.

He co-initiated Djinn Puddle, an online Theory Fiction project. He has co-curated The Pineal Eye (2021), a bid winner and research-based exhibition project supported by Goethe-Institut Peking. Yuhang has contributed to Qilu Criticism, Daoju, and The First Trans—Southeast Asia Triennial research exhibition series. I: Repetition as a gesture towards deep listening (2021) for reviews and fiction writings.

Lee Kai Chung (b.1985, British Hong Kong) is an artist based in Hong Kong. Lee is pursuing a Ph.D. program in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He performs artistic research on historiography, ideology, and time-transcendence of emotion. From his early explorations of archival systems for historiography, Lee has developed an archival methodology that extends to research-based creative practices - including publishing, spatial production, public engagement, and the archives-making. Through performance, moving images, installation and publication, Lee considers the individual gesture as a form of political and artistic transgression, which resonates with existing narratives of history. In 2017, Lee initiated a hexalogy of consecutive projects under the theme of Displacement – to take a departure from the socio-historical implication under the Pan-Asia context, the series examines human conditions and their geopolitical relations arising from dispersion and material flows.

In 2022, Lee is awarded The Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography from Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University, and he received Altius Fellowship from Asian Cultural Council in 2020, the annual Award for Young Artist (Visual Arts) from Hong Kong Arts Development Council and WMA commission Award from WYNG Foundation in 2018.

His recent and upcoming exhibitions include ‘Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present’ (2023), ‘Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur’ (2021) (Winterthur, Switzerland), ‘Seoul Mediacity Biennale 2018’ (Seoul Museum of Art: Seoul, South Korea), ‘12th Shanghai Biennale: Proregress – Art in an Age of Historical Ambivalence’ (2018) (Power Station of Art: Shanghai, China) and ‘Artist Making Movement - Asian Art Biennial 2015’ (2015) (National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts: Taichung, Taiwan). His work The Retrieval, Restoration and Predicament is in the permanent collection of the M+ Museum.

https://www.leekaichung.com/

Yuhang Zhang is a writer and researcher based in London and Guangzhou. Yuhang is currently a PhD student in Goldsmiths, University of London as The Asymmetry PhD Scholarship Scholar. His research and fiction writing centres around theory-fiction and occulture, looking into urban infrastructures and media landscapes in Posthuman Gothic.

He co-initiated Djinn Puddle, an online Theory Fiction project. He has co-curated The Pineal Eye (2021), a bid winner and research-based exhibition project supported by Goethe-Institut Peking. Yuhang has contributed to Qilu Criticism, Daoju, and The First Trans—Southeast Asia Triennial research exhibition series. I: Repetition as a gesture towards deep listening (2021) for reviews and fiction writings.

Tabula Rasa Gallery (London)

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Tuesday - Saturday 12:00 - 18:00 | Sunday - Monday Closed

© 2022 Tabula Rasa Gallery