![]()

IN CONVERSATION WITH

CLARE THACKWAY

Wenxi Liao

26 April 2025

26 April 2025

WL Let’s start from your artistic trajectory. What made you decide to become an artist, and how did your interest in portraiture come about?

CT I grew up in Canberra, which is the capital of Australia, but it's really a big country town. My introduction to portraiture, I guess, was through exhibitions that I saw there at the National Gallery. I remember seeing as a very young child a drawing exhibition by Rubens, and there was also a Rembrandt exhibition, and I was tracing those portraits and just being really obsessed with them. But compared to my kids’ upbringing—growing up in Europe and constantly seeing art in galleries, I had very little access. And I remember as maybe a 15-year-old working at a news agency, and having access to art books, but very, very, very few.

When I do paint portraits, they’re often about a narrative rather than a portrait of that person. I often work with friends, but it is about working through an idea, rather than it being them as a person. Often the genre of portraiture is to represent who that person is through this portrait, but that's not really my interest. It's more about using the body, the hands, or the face as a way of talking about an inner life, but not necessarily a particular person.

WL You mentioned Rubens and Rembrandt. As far as what I can think of in Western art history, the most famous or the named portrait artists are basically male, and compared to their ways of depicting the body, is there any kind of difference in your point of view and approach to that?

CT Absolutely. I think that was really important to me, to think about this embodied experience as a young person coming into my own sense of self, sense of sexuality, and sense of personhood, seeing these representations of women that felt really objectified. It was important for me to be the woman who is painting, but also to feel what it is to be the woman in the painting. I’ve always been very conscious of that sense of objectification, and I worked with my own body a lot because I didn’t want to objectify someone else. I had this strong feeling that I wouldn’t want to do that to another person.

And that is a good reflection—there are so many of these male artists. These grand male artists tend to deal with the big genres—like death and war, and all these sort of grand things—but then women artists are often associated with domestic spaces, or the ‘softer’ spaces—Artemisia Gentileschi for example. But in saying that, when you think about birth and motherhood, those are seen as really domestic—but they are actually the origin of the world. So it’s about giving those things the gravity they truly deserve.

![]()

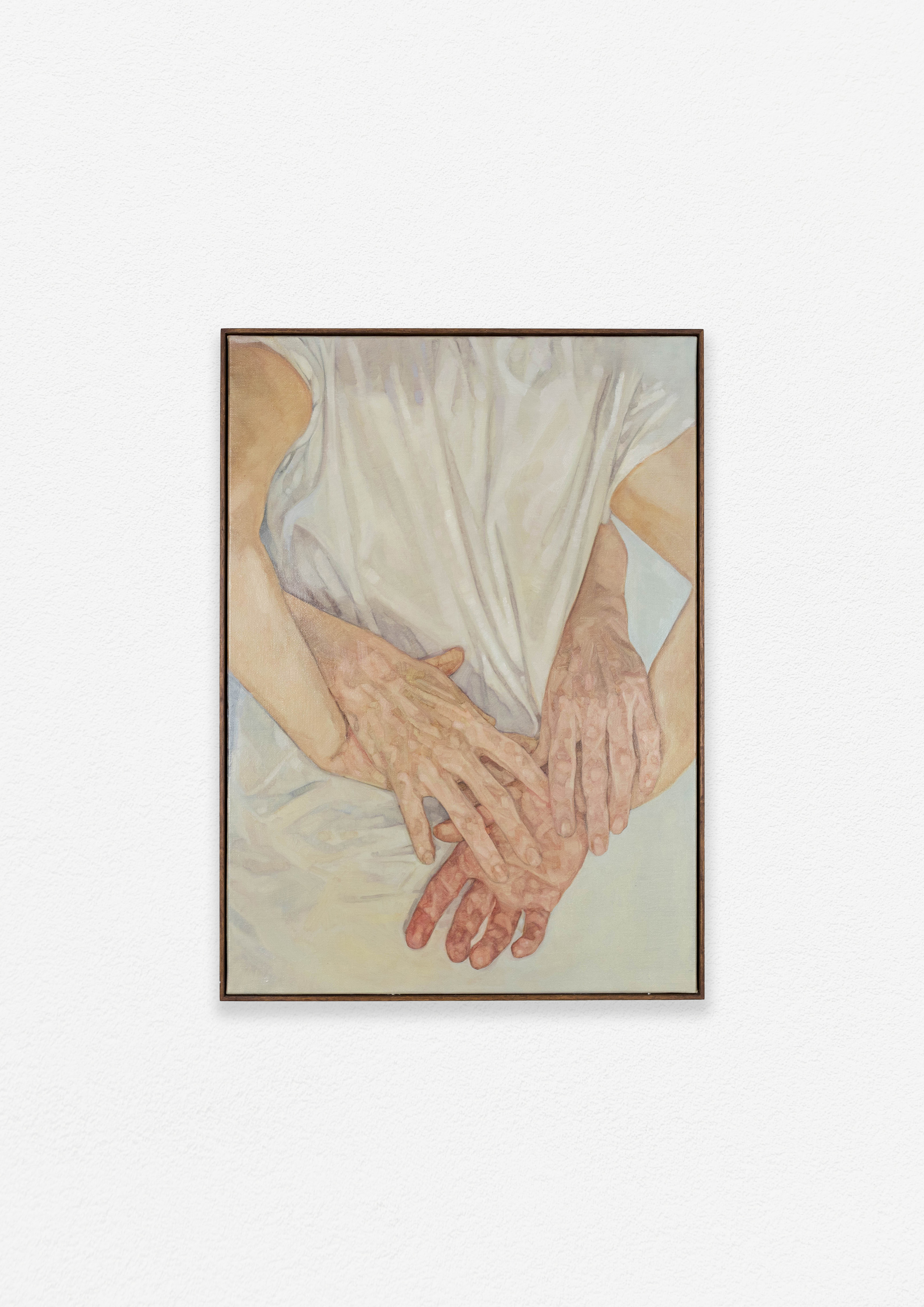

Clare Thackway, How Close Am I to Losing You, oil on linen, 70x50 cm, 2024

WL And how do you approach that? Many of your works are grounded in a very everyday or intimate scope, with subjects that are your friends or the close ones around you, as you’ve just mentioned, while your research around iconography and art-historical references have brought them to a broader context. How do you balance lived experience with research in your practice? Do they feed into each other, or play distinct roles?

CT I think your question is a very beautiful statement in itself, and I feel like you’ve really seen something in the work. It does draw on the personal—on personal history, and current relationships—but also on these grander themes of feminism, art history, and iconography.

Something I don’t talk about a lot is that I grew up in a Christian environment. When I look at these paintings, I think about them from a really personal point of view. I think a lot about my mother’s story, and the oppression she experienced—both within our family structure and within the church we grew up in. So the stories that I’m telling are often very personal to my mother, but at the same time bigger, universal stories. For example, with my recent research into hysteria, I think a lot about the recent advancements in feminism and equal opportunity for women, compared to the centuries, the millennia, when those changes hadn’t yet happened. They’ve only come about in our grandmothers’ or mothers’ lifetimes. There’s a kind of muscle memory—this internalised misogyny, or these patriarchal ideas—that’s still present in how we operate, still embedded in our bodies and our society.

![]()

Clare Thackway, We're Gonna Be Alright, dye on silk, 53x63cm, 2025

WL Do the paintings of hands in this exhibition also reflect that blend of personal experience and symbolic imagery?

CT Well, I don’t really feel like those are related to iconography. Instead, they are a very intimate series, and more about a connection between people. I worked with two friends, and set up a video capturing them moving around. In those works, I was thinking more about gesture than about a grand narrative, or maybe not even narrative at all, really. I also wanted them to feel like love songs in a way—emotional, lyrical. I just wanted them to feel like heartfelt, love song–like works.

I think there’s a huge sense of longing in these works. They might look like intimate portraits, but for me they’re more about loss. When I think about the titles, I realise they speak to letting go, to the breakdown of relationships, to sadness and longing. So, like, We’re Going to Be All Right actually suggests that we’re not. Or Slipping Away from Me refers to the paint, yes, but also that feeling of trying to hold onto a relationship that’s ending. Or Stop the Bleeding—again, it’s about paint, but it’s also emotional. There’s love in them, definitely, but also a lot of longing.

WL What I find interesting is that the way you paint flesh is still quite traditional, in the sense of technique—it feels rooted in a classical approach. But then, through the materiality—especially with the silk—there’s this shift: the bleeding, the unpredictability, the fluidity… It adds something unexpected, something fresh. It pushes the works into a more contemporary space, on both technical and emotive level.

CT I think so too. I guess because my work is so rooted in these traditionally technical ideas, I’m bringing a certain level of skill into the silk paintings—like an understanding of anatomy, an understanding of where I want things to go, and I know that if I make a certain mark, it will look a certain way—because I have that confidence as a painter. But then the dye behaves in such an unpredictable way. I’ll make a mark thinking it’ll be a straight line, and suddenly it becomes a pool of paint. Each pigment behaves differently. One might have a strong staining power and stay in place, while another moves more every time it gets wet, so it keeps reconstituting. That unpredictability is invigorating for me as a painter.

I think for me the silks have been a nice break from oil. With oil painting, I know the process and the materiality very well—I know how to go from A to B—whereas with the silk paintings, because of the way the paint bleeds, I plan the painting as much as I can, but then it just slips away from me. So there’s this sense of chaos, this sense of having to let go and not being able to control it. In a way, that becomes a beautiful kind of symbolism for the flux of life. You try to control everything, and then it just slips away. It feels like a meditation on that idea.

![]()

Clare Thackway, Heavy Lightness, dye on silk, 135x110 cm, 2025

WL So did you have that in mind during the process, or even before the series was created? Or did it emerge along the way?

CT I think it just kind of pops up. I think the way I work is that I don’t plan everything out before I start. Something just starts to emerge. I usually work from an emotional place—this is the feeling I have, and that feeling tends to carry through into the painting. But I don’t go in thinking, I’m going to make a painting about this specific thing, and then do exactly that. It’s more like I come from an intuitive place rather than a strongly conceptual one. But I do tend to return to the same visual language or recurring ideas.

WL And does that apply only to this series, or is that how you usually work? Because, for example, with the snake paintings, I feel like there’s a lot of planning involved, and a lot of research in them. In your creative process, how do you balance that with the more impromptu, emotional side of things, as opposed to the research, or the things you already have in mind?

CT Maybe we need to be specific… So I’ll often look at the story of a saint and feel an affinity with it—not even in a devotional sense, but because there’s something off in the story, something that relates to a person or a relationship in my own life, and I’ll use that. I often have two or three threads going at once: something deeply personal, and something that reflects what I see in society—often from a feminist perspective—and then I use these stories as a kind of bridge. There’s this play, or this layering that I enjoy. I’m not sure exactly how I would describe my approach, but I like that there’s this kind of harmony, like chords playing together—touching on this, touching on that…

WL Absolutely. To me it seems that it’s a kind of projection from your personal history into broader contexts—whether that’s social, religious, or feminist. And especially when you’ve talked about your Christian upbringing, I think these grand, or more contextual, elements have really been embedded in you. Do you relate them to your personal history as well?

CT Yeah, and I think about patterns repeating themselves. I think a lot about epigenetics, about what gets passed down through generations. I also think a lot about what holds still in culture and what evolves and changes. So, like I’ve said, they’re not devotional paintings, they don’t come from a point of personal faith, but they draw on a personal history.

![]()

Clare Thackway, Hold Tight, oil on linen, 146x144cm, 2024

WL Speaking of the theme of intergeneration in your work—especially in the two large oil paintings we’re showing in this exhibition—how do those themes play out for you in those pieces?

CT I think with those two paintings I’ve been really careful not to tell people what they’re about, but instead let them sit in this space of tenderness and tension. It’s always fascinating for me when people come in and respond to the work—it’s almost like a psychoanalytic object. Depending on someone’s relationship with their own mother, they might see it as suffocating, like she’s holding her too tight and the grip is too strong, or they might think, ‘Oh my goodness, they love each other so much.’ I find that really fascinating—there’s this kind of double meaning. I think within intergenerational relationships between women, there are all these beautiful things we pass down, but there’s also pain and trauma in there. While I do work from the personal, I’m not interested in giving the work a didactic meaning—I’m happy for people to bring their own interpretation to it.

![]()

Clare Thackway, All of Me, Oil on linen, 70x50 cm, 2024

WL And do you often play with the sense of narrative in that way? For example, in the other oil paintings—where you leave the body absent, with just the bed sheets. Do you also leave the narrative open?

CT I do. But again, I feel like it doesn’t necessarily have to be like, ‘oh, this was a relationship between these two people.’ I just think it’s kind of—well, I don’t want to use the word ‘universal’ because I think it’s problematic—but I do think the more personal something is, the more it can relate to a broader audience. Because you can see yourself in the person, and the person becomes a kind of universal symbol as you go, ‘I know that feeling, that sense of longing.’ It’s about evoking that feeling, without me needing to spell it out.

![]()

Clare Thackway, Reclamation, oil on linen, 81 x 65 cm, 2024

WL Let’s return to iconography—can we talk about the snake paintings?

CT Absolutely. I started thinking about the snake in Reclamation by going back to the story of Eve—the first woman reaching for knowledge. She’s seduced by the snake, which becomes a symbol of temptation. But what is she tempted by? She’s tempted by knowledge—she wants more. Then she realises she’s naked, she feels shame. It’s a warning to women: don’t want more, stay in your lane. But I’ve also been really interested in how, in other cultures, the snake has a completely different meaning. In the Chinese zodiac, for example, it symbolises regeneration and renewal—shedding skin, rebirth. I was working with that double meaning in the painting. At the opening of this exhibition, I met an art historian who mentioned how, in many pre-Christian, matriarchal cultures, the snake symbolised power, fertility, protection. Only through patriarchal systems did it become this evil figure. She referenced Chinese iconography too—it had the same shift.

And then I got into reading about hysteria. In ancient Greece, they believed the womb could move around the body and cause illness, like this slithering, coiling thing—Aristotle even called it ‘an animal within the animal’. I found that really compelling, how it plays into Christian mythology: the idea that the feminine is animalistic, chaotic, and needs to be controlled. I spent time at the Warburg Institute looking at personified serpents—half-human, half-snake figures. At first, I thought I’d use those as icons, but I found them really disturbing—oppressive and sinister. Even when it’s just a snake, it often has a grimacing, human-like face. That imagery ties into Eve’s banishment—shame and punishment.

WL The half-human, half-serpent image—is it usually a human face on a snake’s body?

CT Yeah, often. A human face, sometimes hands offering the apple or a pear. Even when it’s just a snake, it’s kind of caricatured.

WL That’s so interesting. It reminds me that in pre-patriarchal, ancient Chinese myths, that hybrid image of half human, half serpent deities often represented wisdom and creation. For instance, Nuwa is a goddess who created humans from clay and repaired the sky after it was torn open, and Fuxi, often referred to as a cultural hero or first human king, who taught humans how to live.

CT Are they male and female, or blended?

WL Yes, usually depicted as male and female, often intertwined. Later, the serpent symbolism evolved—on the ‘positive’ side it became the dragon, symbolising royalty, power and fortune, but the snake itself started to represent something negative—danger, poison, evil.

![]()

Clare Thackway, Protection, dye on silk, 53x53 cm, 2025

CT That dichotomy is so fascinating. It reminds me of an Australian Indigenous creation story around a lake. And from the Bible, there’s a story in Numbers: the Israelites are wandering the desert, they sin, and God punishes them with snakes. Then he tells Moses to make a bronze snake on a pole, and whoever looks at it will be healed. So the snake is both punishment and healing—that dual symbolism really interests me. And then I learned about the typology of how the brazen serpent in the Old Testament prefigures the cross. Jesus says, ‘look to the cross and you will be saved,’ echoing that image.

It’s such a powerful symbol across so many cultures. But for me, drawing on a European visual and painting tradition feels natural—it’s part of my own cultural heritage.

WL And here comes my question as well: in all the research you’ve done—looking at the classical Christian iconography from a contemporary perspective and drawing on other cultural references—is it part of your approach to sometimes provoke or even subvert the classics?

CT I think so. But I don’t want to do it in a very brazen or loud way. The works aren’t meant to be sacrilegious or blasphemous. I saw this thing on Instagram where Tracey Emin said, ‘every Easter I paint a crucifix—and it’s the Jesus I’ve never seen before. It’s my Jesus.’ And I think I relate to that. I’m working with these archetypal images—they’re so instantly recognisable, but also deeply impactful. They’re icons for a reason, and they hold a certain power. I think you can embody them in a personal way. That’s really where my interest lies—embodying them and personalising them.

WL Great. Let’s move on to the new series you’ve been working on, which draws from your research into snakes and hysteria—can you tell me more about how that developed?

CT So we talked about that ancient Greek idea of the slithering uterus—the Greek word for uterus is actually the root of ‘hysteria’, so there’s a direct link there. But my way into looking at hysteria really started at my recent visit to the Freud Museum. There was a diagram there showing women in physical poses of hysteria. They’d actually used it as wallpaper in one of the rooms, and it was separated into categories—about four or five—like ‘epileptic’, ‘clownism’, ‘passionate attitudes’, and ‘delirium’. These were exaggerated poses that women were shown in, and I began researching the physicians behind the diagram.

I had assumed hysteria came out of psychoanalysis and early neurology, but it actually has a much older history. As I dug deeper, I found a connection to medieval amulets—these magical objects meant to suppress the wandering womb. They would often feature a Gorgon-like human head with snakes and had poems inscribed on the back, saying: ‘womb black and blackening, you coil like a snake, you roar like a lion, be still like a lamb.’ That was such an unexpected but beautiful link back to the snake symbolism. The physicians who compiled those diagrams were later criticised for only studying women in physical terms, ignoring the full context of their lives, and even for exaggerating or staging the hysteria. It’s a very sad history when you consider how women were persecuted—witch trials, misdiagnosed conditions—all lumped under hysteria. Epilepsy, for example, was seen as a male illness, but in women, similar symptoms were labeled as emotional or spiritual disorders. I feel like I’ve only just scratched the surface of that research, but the symbolic connection to the snake is really compelling.

And from that diagram, I asked my friend Elizabeth—who’s a clinical psychologist—to reenact some of the poses. It was moving, especially given her profession, to think deeply about what those women must have gone through. So far, I’ve made 27 paintings. I’ve been thinking of them almost like 'depositions’—like religious depositions, but of hysteria. Repeated iconography. Some of the poses even mirror religious fanaticism—one reminded me of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, which again makes you wonder: what was really happening to Saint Teresa? Probably hallucinations, intense emotional states. Some poses look like possession—but again, that could be a misunderstood mental health episode. So yes, I’m looking at the history of mental health through this idea of hysteria.

WL And how did hysteria first catch your attention? What made it feel relevant?

CT I’ve always been interested in psychology—I look at it a lot in my research. I think at the core of my practice, I’m trying to represent an inner life. And I use the body to do that—it becomes a vessel or a signal. To me, the body is like a semaphore: it communicates what’s going on inside, emotionally or psychologically. So in that way, hysteria really made sense as a subject—it’s all about the body expressing something deeper.

WL Great. One last question—your residency is coming to an end. How’s the experience been for you?

CT It’s been amazing. Because I live in France, I do have access to museums and collections, but being here in an English-speaking environment, and being able to really deep-dive into research has been incredible. Having access to the Warburg Institute, too—that was a real gift. It gave me time and space to properly explore ideas. Being out of my usual environment allowed me to work deeply, and I feel like I’ve only just tapped into something that could carry me through the next six months of work.

It’s been so valuable just to have that focused time. And the residency has been short enough that it didn’t feel overwhelming—but at the same time, we started with a show and ended with a show, so there was some pressure to produce an outcome. In the end, I only made two new paintings, but began what feels like the start of a much larger project.

CT I grew up in Canberra, which is the capital of Australia, but it's really a big country town. My introduction to portraiture, I guess, was through exhibitions that I saw there at the National Gallery. I remember seeing as a very young child a drawing exhibition by Rubens, and there was also a Rembrandt exhibition, and I was tracing those portraits and just being really obsessed with them. But compared to my kids’ upbringing—growing up in Europe and constantly seeing art in galleries, I had very little access. And I remember as maybe a 15-year-old working at a news agency, and having access to art books, but very, very, very few.

When I do paint portraits, they’re often about a narrative rather than a portrait of that person. I often work with friends, but it is about working through an idea, rather than it being them as a person. Often the genre of portraiture is to represent who that person is through this portrait, but that's not really my interest. It's more about using the body, the hands, or the face as a way of talking about an inner life, but not necessarily a particular person.

WL You mentioned Rubens and Rembrandt. As far as what I can think of in Western art history, the most famous or the named portrait artists are basically male, and compared to their ways of depicting the body, is there any kind of difference in your point of view and approach to that?

CT Absolutely. I think that was really important to me, to think about this embodied experience as a young person coming into my own sense of self, sense of sexuality, and sense of personhood, seeing these representations of women that felt really objectified. It was important for me to be the woman who is painting, but also to feel what it is to be the woman in the painting. I’ve always been very conscious of that sense of objectification, and I worked with my own body a lot because I didn’t want to objectify someone else. I had this strong feeling that I wouldn’t want to do that to another person.

And that is a good reflection—there are so many of these male artists. These grand male artists tend to deal with the big genres—like death and war, and all these sort of grand things—but then women artists are often associated with domestic spaces, or the ‘softer’ spaces—Artemisia Gentileschi for example. But in saying that, when you think about birth and motherhood, those are seen as really domestic—but they are actually the origin of the world. So it’s about giving those things the gravity they truly deserve.

Clare Thackway, How Close Am I to Losing You, oil on linen, 70x50 cm, 2024

WL And how do you approach that? Many of your works are grounded in a very everyday or intimate scope, with subjects that are your friends or the close ones around you, as you’ve just mentioned, while your research around iconography and art-historical references have brought them to a broader context. How do you balance lived experience with research in your practice? Do they feed into each other, or play distinct roles?

CT I think your question is a very beautiful statement in itself, and I feel like you’ve really seen something in the work. It does draw on the personal—on personal history, and current relationships—but also on these grander themes of feminism, art history, and iconography.

Something I don’t talk about a lot is that I grew up in a Christian environment. When I look at these paintings, I think about them from a really personal point of view. I think a lot about my mother’s story, and the oppression she experienced—both within our family structure and within the church we grew up in. So the stories that I’m telling are often very personal to my mother, but at the same time bigger, universal stories. For example, with my recent research into hysteria, I think a lot about the recent advancements in feminism and equal opportunity for women, compared to the centuries, the millennia, when those changes hadn’t yet happened. They’ve only come about in our grandmothers’ or mothers’ lifetimes. There’s a kind of muscle memory—this internalised misogyny, or these patriarchal ideas—that’s still present in how we operate, still embedded in our bodies and our society.

Clare Thackway, We're Gonna Be Alright, dye on silk, 53x63cm, 2025

WL Do the paintings of hands in this exhibition also reflect that blend of personal experience and symbolic imagery?

CT Well, I don’t really feel like those are related to iconography. Instead, they are a very intimate series, and more about a connection between people. I worked with two friends, and set up a video capturing them moving around. In those works, I was thinking more about gesture than about a grand narrative, or maybe not even narrative at all, really. I also wanted them to feel like love songs in a way—emotional, lyrical. I just wanted them to feel like heartfelt, love song–like works.

I think there’s a huge sense of longing in these works. They might look like intimate portraits, but for me they’re more about loss. When I think about the titles, I realise they speak to letting go, to the breakdown of relationships, to sadness and longing. So, like, We’re Going to Be All Right actually suggests that we’re not. Or Slipping Away from Me refers to the paint, yes, but also that feeling of trying to hold onto a relationship that’s ending. Or Stop the Bleeding—again, it’s about paint, but it’s also emotional. There’s love in them, definitely, but also a lot of longing.

WL What I find interesting is that the way you paint flesh is still quite traditional, in the sense of technique—it feels rooted in a classical approach. But then, through the materiality—especially with the silk—there’s this shift: the bleeding, the unpredictability, the fluidity… It adds something unexpected, something fresh. It pushes the works into a more contemporary space, on both technical and emotive level.

CT I think so too. I guess because my work is so rooted in these traditionally technical ideas, I’m bringing a certain level of skill into the silk paintings—like an understanding of anatomy, an understanding of where I want things to go, and I know that if I make a certain mark, it will look a certain way—because I have that confidence as a painter. But then the dye behaves in such an unpredictable way. I’ll make a mark thinking it’ll be a straight line, and suddenly it becomes a pool of paint. Each pigment behaves differently. One might have a strong staining power and stay in place, while another moves more every time it gets wet, so it keeps reconstituting. That unpredictability is invigorating for me as a painter.

I think for me the silks have been a nice break from oil. With oil painting, I know the process and the materiality very well—I know how to go from A to B—whereas with the silk paintings, because of the way the paint bleeds, I plan the painting as much as I can, but then it just slips away from me. So there’s this sense of chaos, this sense of having to let go and not being able to control it. In a way, that becomes a beautiful kind of symbolism for the flux of life. You try to control everything, and then it just slips away. It feels like a meditation on that idea.

Clare Thackway, Heavy Lightness, dye on silk, 135x110 cm, 2025

WL So did you have that in mind during the process, or even before the series was created? Or did it emerge along the way?

CT I think it just kind of pops up. I think the way I work is that I don’t plan everything out before I start. Something just starts to emerge. I usually work from an emotional place—this is the feeling I have, and that feeling tends to carry through into the painting. But I don’t go in thinking, I’m going to make a painting about this specific thing, and then do exactly that. It’s more like I come from an intuitive place rather than a strongly conceptual one. But I do tend to return to the same visual language or recurring ideas.

WL And does that apply only to this series, or is that how you usually work? Because, for example, with the snake paintings, I feel like there’s a lot of planning involved, and a lot of research in them. In your creative process, how do you balance that with the more impromptu, emotional side of things, as opposed to the research, or the things you already have in mind?

CT Maybe we need to be specific… So I’ll often look at the story of a saint and feel an affinity with it—not even in a devotional sense, but because there’s something off in the story, something that relates to a person or a relationship in my own life, and I’ll use that. I often have two or three threads going at once: something deeply personal, and something that reflects what I see in society—often from a feminist perspective—and then I use these stories as a kind of bridge. There’s this play, or this layering that I enjoy. I’m not sure exactly how I would describe my approach, but I like that there’s this kind of harmony, like chords playing together—touching on this, touching on that…

WL Absolutely. To me it seems that it’s a kind of projection from your personal history into broader contexts—whether that’s social, religious, or feminist. And especially when you’ve talked about your Christian upbringing, I think these grand, or more contextual, elements have really been embedded in you. Do you relate them to your personal history as well?

CT Yeah, and I think about patterns repeating themselves. I think a lot about epigenetics, about what gets passed down through generations. I also think a lot about what holds still in culture and what evolves and changes. So, like I’ve said, they’re not devotional paintings, they don’t come from a point of personal faith, but they draw on a personal history.

Clare Thackway, Hold Tight, oil on linen, 146x144cm, 2024

WL Speaking of the theme of intergeneration in your work—especially in the two large oil paintings we’re showing in this exhibition—how do those themes play out for you in those pieces?

CT I think with those two paintings I’ve been really careful not to tell people what they’re about, but instead let them sit in this space of tenderness and tension. It’s always fascinating for me when people come in and respond to the work—it’s almost like a psychoanalytic object. Depending on someone’s relationship with their own mother, they might see it as suffocating, like she’s holding her too tight and the grip is too strong, or they might think, ‘Oh my goodness, they love each other so much.’ I find that really fascinating—there’s this kind of double meaning. I think within intergenerational relationships between women, there are all these beautiful things we pass down, but there’s also pain and trauma in there. While I do work from the personal, I’m not interested in giving the work a didactic meaning—I’m happy for people to bring their own interpretation to it.

Clare Thackway, All of Me, Oil on linen, 70x50 cm, 2024

WL And do you often play with the sense of narrative in that way? For example, in the other oil paintings—where you leave the body absent, with just the bed sheets. Do you also leave the narrative open?

CT I do. But again, I feel like it doesn’t necessarily have to be like, ‘oh, this was a relationship between these two people.’ I just think it’s kind of—well, I don’t want to use the word ‘universal’ because I think it’s problematic—but I do think the more personal something is, the more it can relate to a broader audience. Because you can see yourself in the person, and the person becomes a kind of universal symbol as you go, ‘I know that feeling, that sense of longing.’ It’s about evoking that feeling, without me needing to spell it out.

Clare Thackway, Reclamation, oil on linen, 81 x 65 cm, 2024

WL Let’s return to iconography—can we talk about the snake paintings?

CT Absolutely. I started thinking about the snake in Reclamation by going back to the story of Eve—the first woman reaching for knowledge. She’s seduced by the snake, which becomes a symbol of temptation. But what is she tempted by? She’s tempted by knowledge—she wants more. Then she realises she’s naked, she feels shame. It’s a warning to women: don’t want more, stay in your lane. But I’ve also been really interested in how, in other cultures, the snake has a completely different meaning. In the Chinese zodiac, for example, it symbolises regeneration and renewal—shedding skin, rebirth. I was working with that double meaning in the painting. At the opening of this exhibition, I met an art historian who mentioned how, in many pre-Christian, matriarchal cultures, the snake symbolised power, fertility, protection. Only through patriarchal systems did it become this evil figure. She referenced Chinese iconography too—it had the same shift.

And then I got into reading about hysteria. In ancient Greece, they believed the womb could move around the body and cause illness, like this slithering, coiling thing—Aristotle even called it ‘an animal within the animal’. I found that really compelling, how it plays into Christian mythology: the idea that the feminine is animalistic, chaotic, and needs to be controlled. I spent time at the Warburg Institute looking at personified serpents—half-human, half-snake figures. At first, I thought I’d use those as icons, but I found them really disturbing—oppressive and sinister. Even when it’s just a snake, it often has a grimacing, human-like face. That imagery ties into Eve’s banishment—shame and punishment.

WL The half-human, half-serpent image—is it usually a human face on a snake’s body?

CT Yeah, often. A human face, sometimes hands offering the apple or a pear. Even when it’s just a snake, it’s kind of caricatured.

WL That’s so interesting. It reminds me that in pre-patriarchal, ancient Chinese myths, that hybrid image of half human, half serpent deities often represented wisdom and creation. For instance, Nuwa is a goddess who created humans from clay and repaired the sky after it was torn open, and Fuxi, often referred to as a cultural hero or first human king, who taught humans how to live.

CT Are they male and female, or blended?

WL Yes, usually depicted as male and female, often intertwined. Later, the serpent symbolism evolved—on the ‘positive’ side it became the dragon, symbolising royalty, power and fortune, but the snake itself started to represent something negative—danger, poison, evil.

Clare Thackway, Protection, dye on silk, 53x53 cm, 2025

CT That dichotomy is so fascinating. It reminds me of an Australian Indigenous creation story around a lake. And from the Bible, there’s a story in Numbers: the Israelites are wandering the desert, they sin, and God punishes them with snakes. Then he tells Moses to make a bronze snake on a pole, and whoever looks at it will be healed. So the snake is both punishment and healing—that dual symbolism really interests me. And then I learned about the typology of how the brazen serpent in the Old Testament prefigures the cross. Jesus says, ‘look to the cross and you will be saved,’ echoing that image.

It’s such a powerful symbol across so many cultures. But for me, drawing on a European visual and painting tradition feels natural—it’s part of my own cultural heritage.

WL And here comes my question as well: in all the research you’ve done—looking at the classical Christian iconography from a contemporary perspective and drawing on other cultural references—is it part of your approach to sometimes provoke or even subvert the classics?

CT I think so. But I don’t want to do it in a very brazen or loud way. The works aren’t meant to be sacrilegious or blasphemous. I saw this thing on Instagram where Tracey Emin said, ‘every Easter I paint a crucifix—and it’s the Jesus I’ve never seen before. It’s my Jesus.’ And I think I relate to that. I’m working with these archetypal images—they’re so instantly recognisable, but also deeply impactful. They’re icons for a reason, and they hold a certain power. I think you can embody them in a personal way. That’s really where my interest lies—embodying them and personalising them.

WL Great. Let’s move on to the new series you’ve been working on, which draws from your research into snakes and hysteria—can you tell me more about how that developed?

CT So we talked about that ancient Greek idea of the slithering uterus—the Greek word for uterus is actually the root of ‘hysteria’, so there’s a direct link there. But my way into looking at hysteria really started at my recent visit to the Freud Museum. There was a diagram there showing women in physical poses of hysteria. They’d actually used it as wallpaper in one of the rooms, and it was separated into categories—about four or five—like ‘epileptic’, ‘clownism’, ‘passionate attitudes’, and ‘delirium’. These were exaggerated poses that women were shown in, and I began researching the physicians behind the diagram.

I had assumed hysteria came out of psychoanalysis and early neurology, but it actually has a much older history. As I dug deeper, I found a connection to medieval amulets—these magical objects meant to suppress the wandering womb. They would often feature a Gorgon-like human head with snakes and had poems inscribed on the back, saying: ‘womb black and blackening, you coil like a snake, you roar like a lion, be still like a lamb.’ That was such an unexpected but beautiful link back to the snake symbolism. The physicians who compiled those diagrams were later criticised for only studying women in physical terms, ignoring the full context of their lives, and even for exaggerating or staging the hysteria. It’s a very sad history when you consider how women were persecuted—witch trials, misdiagnosed conditions—all lumped under hysteria. Epilepsy, for example, was seen as a male illness, but in women, similar symptoms were labeled as emotional or spiritual disorders. I feel like I’ve only just scratched the surface of that research, but the symbolic connection to the snake is really compelling.

And from that diagram, I asked my friend Elizabeth—who’s a clinical psychologist—to reenact some of the poses. It was moving, especially given her profession, to think deeply about what those women must have gone through. So far, I’ve made 27 paintings. I’ve been thinking of them almost like 'depositions’—like religious depositions, but of hysteria. Repeated iconography. Some of the poses even mirror religious fanaticism—one reminded me of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, which again makes you wonder: what was really happening to Saint Teresa? Probably hallucinations, intense emotional states. Some poses look like possession—but again, that could be a misunderstood mental health episode. So yes, I’m looking at the history of mental health through this idea of hysteria.

WL And how did hysteria first catch your attention? What made it feel relevant?

CT I’ve always been interested in psychology—I look at it a lot in my research. I think at the core of my practice, I’m trying to represent an inner life. And I use the body to do that—it becomes a vessel or a signal. To me, the body is like a semaphore: it communicates what’s going on inside, emotionally or psychologically. So in that way, hysteria really made sense as a subject—it’s all about the body expressing something deeper.

WL Great. One last question—your residency is coming to an end. How’s the experience been for you?

CT It’s been amazing. Because I live in France, I do have access to museums and collections, but being here in an English-speaking environment, and being able to really deep-dive into research has been incredible. Having access to the Warburg Institute, too—that was a real gift. It gave me time and space to properly explore ideas. Being out of my usual environment allowed me to work deeply, and I feel like I’ve only just tapped into something that could carry me through the next six months of work.

It’s been so valuable just to have that focused time. And the residency has been short enough that it didn’t feel overwhelming—but at the same time, we started with a show and ended with a show, so there was some pressure to produce an outcome. In the end, I only made two new paintings, but began what feels like the start of a much larger project.

Tabula Rasa Gallery (London)

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Tuesday - Saturday 12:00 - 18:00 | Sunday - Monday Closed

© 2022 Tabula Rasa Gallery