Running Up That Hill

Julia Long, solo

Tabula Rasa Gallery | London

22 June - 31 July, 2024

Julia Long, solo

Tabula Rasa Gallery | London

22 June - 31 July, 2024

In the exhibition “Running Up That Hill” at Tabula Rasa Gallery, London, UK, a new series of works explores the discursive themes surrounding the roles and scripts of women and

transcultural womanhood, as Julia Long (b. 1984, Chongqing, China) presents her first UK solo gallery show. An artist, translator, and historian, Long interweaves her family history, academic background, and diverse practices into her body of works, reflecting on the multifaceted roles she embodies. This making of the series of works comes at a critical moment as her home country's leadership attempts to redefine the concept of women's roles. Departing from the traditional fine art paradigm, Julia Long mobilises her multiple "roles" to convey her system of discursive works through various forms, including art, literature, and a range of interdisciplinary collaborations.

Background and Influences

Born into an artistic family in Chongqing, China, Julia Long is part of a lineage steeped in the arts. Her grandparents and parents were and are all artists associated with the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, one of China’s "Eight Great Art Academies" modelled after Soviet institutions. Her grandfather, Long Shi, was a revolutionary who joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1939 and worked as a journalist and army magazine editor-in-chief; he later became the principal of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute after restoring the college entrance examination system in 1978. Her father, Long Quan, and her mother, Li Zhen, have both taught at the affiliated high school and the Institute itself, nurturing generations of Chinese contemporary artists who have been active both in China and internationally. Their family history encapsulates a microcosm of modern Chinese history, spanning the brief modernisation of the Republic era, the Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese Civil War, and the subsequent political movements following the establishment of the People's Republic of China, leading up to the Reform and Opening-up period.

Despite her artistic lineage, Julia Long was not formally trained as an artist. Instead, she pursued her education in history at Nankai University in Tianjin, China—a university founded by Chinese modern educator and gender reformist Yan Xiu following the failure of the Hundred Days' Reform, aimed at establishing a new education system in the Western-dominated concession areas of Tianjin in 1904. Long furthered her studies in the United States at the University of Georgia in Athens, GA, focusing on American gender history.

![Julia LongThe Bird in the Park Doesn’t Understand Neither120 x 90 cm2024]()

![Installation view]()

![Julia LongChole90 x 70 cmoil on canvas2024]()

![Julia LongRepublican Wonderwoman Motherhoodwatercolour on paper76 x 56 cm2024]()

Nevertheless, her foundation in art education, imparted by her parents and the family legacy and academic system they represent, ensured that artistic creation, primarily drawing and painting, remained a major medium of expression for Julia Long. This artistic practice, combined with her writing and social activism, positions her as a multifaceted creator practising outside both the official Chinese art system and the conventional framework of professional Chinese contemporary artists.

Historical Context and Inspirations

Viewed through the lens of Chinese history, Julia Long's identity and family history evoke the "hidden" female creators and roles from the late Qing Dynasty to the pre-Reform and Opening-up era. These include figures like Shen Zufeng (1909-1977), a translator and prominent scholar in modern and contemporary ci poetry, and the wife of renowned scholar Cheng Qianfan. Her life spanned from modern to contemporary times, witnessing the War of Resistance against Japan, the Chinese Civil War, the establishment of the People's Republic of China, and the Cultural Revolution. Her poetry is known for its sincere emotions and elegant, refined language.

Another such figure is Jiang Yan (1919-1958), a modern painter known for her work "Asking Mom Questions" (in the permanent collection of the National Art Museum of China). This piece, painted in the style of Chinese nianhua (Chinese New Year picture) style but influenced by Soviet aesthetics post the founding of the People's Republic of China, depicts the daily life of a mother and daughter in rural northern China. Before and after this, there were no specific works dedicated to only portraying women for a long period.

![]()

Julia Long's work resonates with these forgotten narratives, bridging the gap between past and present and bringing to light the contributions of these overlooked female creators.

Western Perspectives and Globalised Contexts

From a Western historical perspective and through the lens of contemporary, globalised views, Julia Long integrates the gender history of the West, including the United States, with female roles in popular fairy tales and pop culture into her discursive works and research subjects. After completing her studies in Georgia, Long embarked on a dual life of creating art and writing while working as a publicist for renowned New York restaurants. She later returned to Beijing, China, to work at the K11 Kunsthalle, founded by retail mogul Adrian Cheng. Julia Long was a professional woman earning a living in the real world, in real-time, experiencing and observing the evolving roles of women in a multitude of professional spheres.

Although, in recent years, she has focused more on her art and writing and less on pursuing employment, she remains different from professional artists in the field of contemporary art. Her art and writings reach a broader audience through mainstream Chinese media outlets such as GQ China and Yueshi Epicure, typically with hundreds of thousands if not millions of copies in circulation and online readers. These works particularly resonate with a readership of urban “white-collar” professional women in megacities like Beijing and Shanghai. Her various collaborations include long-term projects with Hong Kong’s homegrown luxury brand Shanghai Tang, creating Chinese New Year-themed products, and partnerships with the socialite and fashion blogger Teresa Cheung.

These collaborations expand her artistic vision and concepts into the realm of “pop aesthetics," ensuring that her art and creations step out of the ivory tower and carry an anti-elitist spark.

![]()

All these elements—Julia Long's artistic process and discursive themes—are integrated into the series of works and the exhibition “Running Up That Hill”, a title taken from English singer-songwriter Kate Bush’s song1, revolving around the desire to understand and empathise with another person’s experiences and emotions. In the new series of works on roles, scripts and womanhood, she embodies multiple "female roles," yet fundamentally, she is "anti-script": hailing from an artistic family but not directly becoming an artist; engaging in academic research without retreating into an academic bubble; finding alternative ways to communicate her work outside of rigid systems. But her academic training in history has also contributed to her consistent effort of avoiding solipsism in her works but rather focusing more on women’s collective history and individual stories, because writing in history requires one to avboid using the first person singular of “I”. Ultimately, in "Roles and Scripts of Women," she refrains from narrating her own story or script, avoiding self-iconisation in an era that is full of self-promotion.

The exhibition “Running Up That Hill” in London is neither the beginning nor the end of Julia Long's discursive journey. It is merely a point where her systematic thoughts on the social constructions of gender roles take shape and become increasingly urgent. Much like Spanish writer and philosopher Paul B. Preciado, who critiques traditional binary gender notions and argues that gender is not a biological necessity but a social and political construct, Long's work reflects on similar themes. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the propaganda "Women hold up half the sky" emphasised that women not only makeup almost half of the population but also play an equally important role in daily life, nation-building, and social development. However, as China faces a population crisis, with a decline for the first time since the 1960s, officials have started to downplay "women hold up half the sky” and any possible gender equality issues. Instead, they focus on promoting the goals set for Chinese women under "the essential content of Chinese-style modernisation": marriage and childbirth.

The exhibition is divided into three parts: Childhood Myths, Self Definition, and Life Choices.

Childhood Myths

Julia Long's body of works is not merely an exploration of gender roles but a profound critique of the narratives that shape them. Reflecting on childhood myths, she examines the portrayal of female characters in Western fairy tales, using "The Frog Prince"2 as a prime example. In the familiar version of the story, even a slimy, sticky frog plays the role of the savior, retrieving the princess's golden ball but demanding a kiss or a night on her pillow in return. As a child, Long found the frog's demands outrageous; even if the princess complied and he turned into a prince, it was still an unreasonable frog making selfish demands.

![]()

Julia Long, The Princess’ Revenge, 61 x 46 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

Later in her college years, through academic texts, Long discovered the original version of the story, where the princess, fed up with the frog's unreasonable requests, throws him against the wall, transforming him into a prince. Why had this straightforward, logical reaction not endured, while the version where the princess becomes increasingly obliging had? This evolution of fairy tales reflects the societal conditioning of female behavior. If the suitor is a prince, the princess is expected to acquiesce to his demands, even if she has many golden balls, symbolising her pursuits and control over her life.

From a young age, Julia Long created stretches and drawings based on princesses or "princess dress" female characters. By comparing her childhood creations with her current works, it is evident that these characters were not stereotypical princesses with doll-like faces but rather brave women, reflecting her early imagination of mature women's lives. As she grew up, the women she depicted continued to embody the same courage and fearlessness she had always envisioned.

![]()

left: early sketches of “princess” by Julia Long

right: Julia Long, Quest for the Rose 02, 76 x 56 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

Self Definition

During her ongoing translation work, Julia Long came across the essay "Peonies,"3 written by the renowned British novelist Zadie Smith. This essay, along with the enduring themes in Smith's work, inspired a series of creations by Long. Written in the spring of 2020, the essay describes how the pandemic disrupted Smith's busy routine of childcare, teaching, and writing while living in New York. One day, she found herself with the rare opportunity to stop and admire the tulips in Jefferson Market Garden, a small square garden next to the library at the corner of Sixth Avenue and West 8th Street in Greenwich Village. Normally, this time would be spent rushing for coffee and attending to her hectic schedule. She wasn't alone in her admiration; two other unknown women were also appreciating the flowers.

![]()

(from left to right)

Julia Long, Which Kind of Flowers Are You, 56 x 76 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

Julia Long, Zadie Smith, 90 x 60 cm, oil on canvas, 2024

Julia Long, Tunip or Peony, 61 x 46 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

The scene and the flowers sparked a thought in Smith. She felt that women’s lives are often predetermined to fit a certain mold: if you see tulips, you must become a tulip. But she rejected this notion, insisting that if she saw peonies, then she was destined to become a peony. In Julia Long’s view, our lives are similar; navigating the balance between personal choice, objective circumstances, and external expectations to take control of our destiny and become the flower we wish to be is no easy task. Though tulips and peonies are undeniably different species in botany, these given names symbolise the constraints imposed on us, much like the socially constructed gender roles that extend beyond biology.

Julia Long often uses New York City, a metropolis she lived in, as the backdrop for her art. The convergence of her reading and artistic practice evokes thoughts and narratives that transcend time and space, breaking down barriers between Eastern and Western societies, especially in regions with contrasting ideologies and attitudes towards gender issues.

Life Choices

In "Childhood Myths," Julia Long establishes the foundation for her dialectical thinking and fundamental gender perspectives by comparing works created in different eras that share striking similarities. Moving to “Self Definition," she incorporates Ludwig Wittgenstein's language games and contemporary gender theorists' views, including Paul B. Preciado’s theories on gender as a social construct, to form new insights, all set in her classic “New York City” and literary arenas. If the first two parts serve as a prelude, the final section, "Life Choices," sees Julia Long expand to create a complex universe of gender discourses.

From her childhood memories of seeing the book "Good Girls Go to Heaven, Bad Girls Go Everywhere"4 on her parents' bookshelf to Laurel Ulrich's "Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History"5, a declaration of female rebellious spirit, in her research deck; from the historical and cultural regulation of ideal female roles—Amazonian warriors needing to cut off a breast, colonial—era witch hunts punishing rebellious women, to the early American concept of "Republican Motherhood." Not surprisingly, Wonder Woman, during the 1950s, was depowered to be office secretary, an attempt to make her more relatable. While translating works like Joan Didion in “The Paris Review,”6 she reflected on the typical images of male writers like Hemingway—dashing, reckless, fearless—while female writers had to create in secrecy. Writing for women was seen as rebellious; being oneself was even a luxury. Women were expected to sacrifice themselves to meet societal expectations but were not allowed to be themselves.

![]()

The climax of this section and indeed the entire exhibition is the painting "Mirror of the Times." This piece draws inspiration from an old mirror in a friend's colonial mansion in Shanghai, reflecting three female figures: Julia Long’s great-grandmother, who was an artist before becoming a mother and ultimately chose marriage; her grandmother, who followed her husband's lead in life, resulting in various disappointments; and Miss Wang from "Blossoms,"7 written by Jin Yucheng, representing the current generation of women who can choose for themselves and become their own anchors.

![]()

Julia Long, The Mirror of Times, 76 x 56 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

From New York City to Beijing, Julia Long constructs an ever-expanding universe focused on gender issues, forming a more systematic body of discursive works. The new series on view, her ongoing artistic practice, research, translations, original writings, and numerous cross-disciplinary collaborations continuously explore gender roles, transcultural narratives, and the complex interplay between individual choice and societal expectations. Through the gaze of various female characters in the exhibition, viewers can glimpse and imagine the interiors, delving further into this intricate discourse. This foundation supports progressive gender issues in social movements worldwide and serves as a tool to identify and call out potential regressions in these efforts.

Zong Han

June 9th, 2024

on the train from Munich, Germany to Basel, Switzerland

[1] Kate Bush, “Running Up That Hill,” on Hounds of Love, 1985.

[2] Brothers Grimm, “The Frog Prince,” in Grimm’s Fairy Tales, 1812.

[3] Zadie Smith, “Peonies,” in Intimations: Six Essays (New York: Penguin Books, 2020).

[4] Jana U. Ehrhardt, Good Girls Go to Heaven, Bad Girls Go Everywhere (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997).

[5] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History (New York: Vintage, 2008).

[6] Joan Didion, “The Art of Fiction No.71,” interviewed by Linda Kuehl, The Paris Review, no.74 (Fall-Winter 1978).

[7] Jin Yucheng, Blossoms (Shanghai literature and Art Publishing House, 2012). Blossoms is intricate portrayal of Shanghai’s social and cultural transformation from the 1960s to the 1990s, woven through the lives of various interconnected characters.

About the Writer

Zong HAN is a culture strategist, advisor and writer based in Singapore.

About the Artist

Julia (Di) Long (b.1984, China) is an artist currently working and living in Beijing China. Born in a family of three generations’ practice in arts, she has chosen a discursive path that later led her way to the art world. Long earned her bachelor degree with highest honor in world history from Nankai University in Tianjin China, furthered her study in American history and gender history in University of Georgia with a full scholarship. She then moved to New York and worked as a restaurant publicist, while making art, doing illustration for magazines, translating articles, and hosting a podcast.

Long has shifted her focus mainly on art in 2017, since then she has done three solo exhibitions at Tabula Rasa Gallery Beijing, along with her translation works of female writers and her writings with a gender focus, she has thus formatted her discursive themes of artistic endeavors into a universe focusing on the discussion on feminism, women’s history and experiences, with an intercultural perspective based on her academic background and personal observation.

Selected solo exhibitions include: If We Could Swap Our Places, with Tabula Rasa Gallery & Bao Collection Space (Upcoming, Shanghai 2024); Running Up That Hill, Tabula Rasa Gallery(London 2024), Provisional Emotions, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2021); Meanwhile, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2019); One Eighth of the Narrative, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2017); Serendipity, UNdefine (Shanghai, 2014); Selected group shows include: Home Sweet Home, Power Station of Art (Shanghai 2017); Nián Nián :The Power and Agency of Animal Forms, (Deji Museum, 2023).

Publication: Distracted, an essay collection (Guangxi Normal University Press, 2021) Selected translation publication include: Joan Didion’s two Paris Review interviews ( The Art of Fiction No.71, and The Art of Non-fiction No. 1) ; Hilary Mantel, Paris Review interview ( The Art of Fiction, No. 226), Chinese version published in 2020. Patti Smith, Devotion( Why I Write), (Yale University Press, 2017), Chinese version published in 2021.

Background and Influences

Born into an artistic family in Chongqing, China, Julia Long is part of a lineage steeped in the arts. Her grandparents and parents were and are all artists associated with the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, one of China’s "Eight Great Art Academies" modelled after Soviet institutions. Her grandfather, Long Shi, was a revolutionary who joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1939 and worked as a journalist and army magazine editor-in-chief; he later became the principal of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute after restoring the college entrance examination system in 1978. Her father, Long Quan, and her mother, Li Zhen, have both taught at the affiliated high school and the Institute itself, nurturing generations of Chinese contemporary artists who have been active both in China and internationally. Their family history encapsulates a microcosm of modern Chinese history, spanning the brief modernisation of the Republic era, the Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese Civil War, and the subsequent political movements following the establishment of the People's Republic of China, leading up to the Reform and Opening-up period.

Despite her artistic lineage, Julia Long was not formally trained as an artist. Instead, she pursued her education in history at Nankai University in Tianjin, China—a university founded by Chinese modern educator and gender reformist Yan Xiu following the failure of the Hundred Days' Reform, aimed at establishing a new education system in the Western-dominated concession areas of Tianjin in 1904. Long furthered her studies in the United States at the University of Georgia in Athens, GA, focusing on American gender history.

Nevertheless, her foundation in art education, imparted by her parents and the family legacy and academic system they represent, ensured that artistic creation, primarily drawing and painting, remained a major medium of expression for Julia Long. This artistic practice, combined with her writing and social activism, positions her as a multifaceted creator practising outside both the official Chinese art system and the conventional framework of professional Chinese contemporary artists.

Historical Context and Inspirations

Viewed through the lens of Chinese history, Julia Long's identity and family history evoke the "hidden" female creators and roles from the late Qing Dynasty to the pre-Reform and Opening-up era. These include figures like Shen Zufeng (1909-1977), a translator and prominent scholar in modern and contemporary ci poetry, and the wife of renowned scholar Cheng Qianfan. Her life spanned from modern to contemporary times, witnessing the War of Resistance against Japan, the Chinese Civil War, the establishment of the People's Republic of China, and the Cultural Revolution. Her poetry is known for its sincere emotions and elegant, refined language.

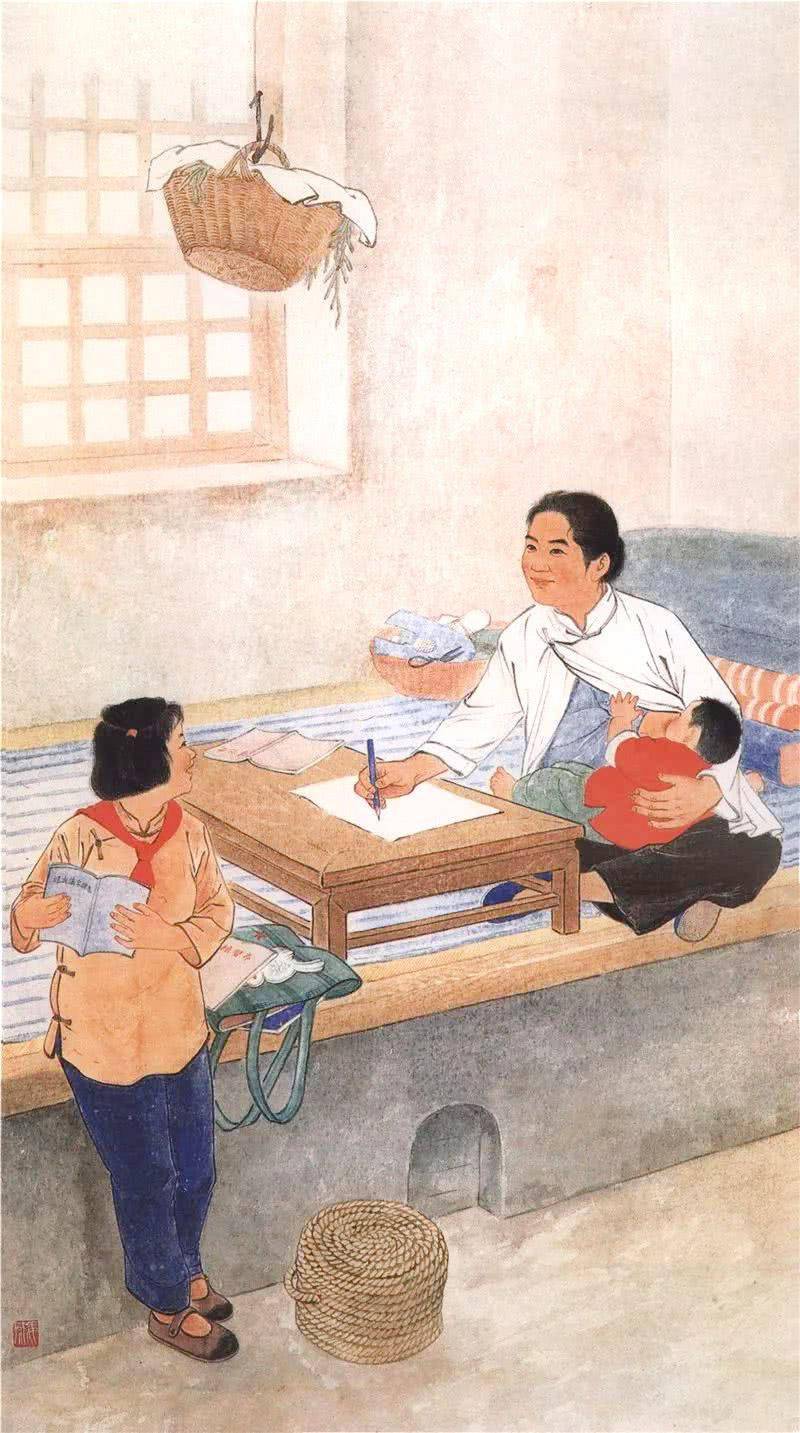

Another such figure is Jiang Yan (1919-1958), a modern painter known for her work "Asking Mom Questions" (in the permanent collection of the National Art Museum of China). This piece, painted in the style of Chinese nianhua (Chinese New Year picture) style but influenced by Soviet aesthetics post the founding of the People's Republic of China, depicts the daily life of a mother and daughter in rural northern China. Before and after this, there were no specific works dedicated to only portraying women for a long period.

Jiang Yan, Asking Mom Questions, 113.6 x 64.6 cm, watercolour on paper, 1953

collection of National Art Museum of China

collection of National Art Museum of China

Julia Long's work resonates with these forgotten narratives, bridging the gap between past and present and bringing to light the contributions of these overlooked female creators.

Western Perspectives and Globalised Contexts

From a Western historical perspective and through the lens of contemporary, globalised views, Julia Long integrates the gender history of the West, including the United States, with female roles in popular fairy tales and pop culture into her discursive works and research subjects. After completing her studies in Georgia, Long embarked on a dual life of creating art and writing while working as a publicist for renowned New York restaurants. She later returned to Beijing, China, to work at the K11 Kunsthalle, founded by retail mogul Adrian Cheng. Julia Long was a professional woman earning a living in the real world, in real-time, experiencing and observing the evolving roles of women in a multitude of professional spheres.

Although, in recent years, she has focused more on her art and writing and less on pursuing employment, she remains different from professional artists in the field of contemporary art. Her art and writings reach a broader audience through mainstream Chinese media outlets such as GQ China and Yueshi Epicure, typically with hundreds of thousands if not millions of copies in circulation and online readers. These works particularly resonate with a readership of urban “white-collar” professional women in megacities like Beijing and Shanghai. Her various collaborations include long-term projects with Hong Kong’s homegrown luxury brand Shanghai Tang, creating Chinese New Year-themed products, and partnerships with the socialite and fashion blogger Teresa Cheung.

These collaborations expand her artistic vision and concepts into the realm of “pop aesthetics," ensuring that her art and creations step out of the ivory tower and carry an anti-elitist spark.

All these elements—Julia Long's artistic process and discursive themes—are integrated into the series of works and the exhibition “Running Up That Hill”, a title taken from English singer-songwriter Kate Bush’s song1, revolving around the desire to understand and empathise with another person’s experiences and emotions. In the new series of works on roles, scripts and womanhood, she embodies multiple "female roles," yet fundamentally, she is "anti-script": hailing from an artistic family but not directly becoming an artist; engaging in academic research without retreating into an academic bubble; finding alternative ways to communicate her work outside of rigid systems. But her academic training in history has also contributed to her consistent effort of avoiding solipsism in her works but rather focusing more on women’s collective history and individual stories, because writing in history requires one to avboid using the first person singular of “I”. Ultimately, in "Roles and Scripts of Women," she refrains from narrating her own story or script, avoiding self-iconisation in an era that is full of self-promotion.

The exhibition “Running Up That Hill” in London is neither the beginning nor the end of Julia Long's discursive journey. It is merely a point where her systematic thoughts on the social constructions of gender roles take shape and become increasingly urgent. Much like Spanish writer and philosopher Paul B. Preciado, who critiques traditional binary gender notions and argues that gender is not a biological necessity but a social and political construct, Long's work reflects on similar themes. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the propaganda "Women hold up half the sky" emphasised that women not only makeup almost half of the population but also play an equally important role in daily life, nation-building, and social development. However, as China faces a population crisis, with a decline for the first time since the 1960s, officials have started to downplay "women hold up half the sky” and any possible gender equality issues. Instead, they focus on promoting the goals set for Chinese women under "the essential content of Chinese-style modernisation": marriage and childbirth.

The exhibition is divided into three parts: Childhood Myths, Self Definition, and Life Choices.

Childhood Myths

Julia Long's body of works is not merely an exploration of gender roles but a profound critique of the narratives that shape them. Reflecting on childhood myths, she examines the portrayal of female characters in Western fairy tales, using "The Frog Prince"2 as a prime example. In the familiar version of the story, even a slimy, sticky frog plays the role of the savior, retrieving the princess's golden ball but demanding a kiss or a night on her pillow in return. As a child, Long found the frog's demands outrageous; even if the princess complied and he turned into a prince, it was still an unreasonable frog making selfish demands.

Julia Long, The Princess’ Revenge, 61 x 46 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

Later in her college years, through academic texts, Long discovered the original version of the story, where the princess, fed up with the frog's unreasonable requests, throws him against the wall, transforming him into a prince. Why had this straightforward, logical reaction not endured, while the version where the princess becomes increasingly obliging had? This evolution of fairy tales reflects the societal conditioning of female behavior. If the suitor is a prince, the princess is expected to acquiesce to his demands, even if she has many golden balls, symbolising her pursuits and control over her life.

From a young age, Julia Long created stretches and drawings based on princesses or "princess dress" female characters. By comparing her childhood creations with her current works, it is evident that these characters were not stereotypical princesses with doll-like faces but rather brave women, reflecting her early imagination of mature women's lives. As she grew up, the women she depicted continued to embody the same courage and fearlessness she had always envisioned.

left: early sketches of “princess” by Julia Long

right: Julia Long, Quest for the Rose 02, 76 x 56 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

Self Definition

During her ongoing translation work, Julia Long came across the essay "Peonies,"3 written by the renowned British novelist Zadie Smith. This essay, along with the enduring themes in Smith's work, inspired a series of creations by Long. Written in the spring of 2020, the essay describes how the pandemic disrupted Smith's busy routine of childcare, teaching, and writing while living in New York. One day, she found herself with the rare opportunity to stop and admire the tulips in Jefferson Market Garden, a small square garden next to the library at the corner of Sixth Avenue and West 8th Street in Greenwich Village. Normally, this time would be spent rushing for coffee and attending to her hectic schedule. She wasn't alone in her admiration; two other unknown women were also appreciating the flowers.

(from left to right)

Julia Long, Which Kind of Flowers Are You, 56 x 76 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

Julia Long, Zadie Smith, 90 x 60 cm, oil on canvas, 2024

Julia Long, Tunip or Peony, 61 x 46 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

The scene and the flowers sparked a thought in Smith. She felt that women’s lives are often predetermined to fit a certain mold: if you see tulips, you must become a tulip. But she rejected this notion, insisting that if she saw peonies, then she was destined to become a peony. In Julia Long’s view, our lives are similar; navigating the balance between personal choice, objective circumstances, and external expectations to take control of our destiny and become the flower we wish to be is no easy task. Though tulips and peonies are undeniably different species in botany, these given names symbolise the constraints imposed on us, much like the socially constructed gender roles that extend beyond biology.

Julia Long often uses New York City, a metropolis she lived in, as the backdrop for her art. The convergence of her reading and artistic practice evokes thoughts and narratives that transcend time and space, breaking down barriers between Eastern and Western societies, especially in regions with contrasting ideologies and attitudes towards gender issues.

Life Choices

In "Childhood Myths," Julia Long establishes the foundation for her dialectical thinking and fundamental gender perspectives by comparing works created in different eras that share striking similarities. Moving to “Self Definition," she incorporates Ludwig Wittgenstein's language games and contemporary gender theorists' views, including Paul B. Preciado’s theories on gender as a social construct, to form new insights, all set in her classic “New York City” and literary arenas. If the first two parts serve as a prelude, the final section, "Life Choices," sees Julia Long expand to create a complex universe of gender discourses.

From her childhood memories of seeing the book "Good Girls Go to Heaven, Bad Girls Go Everywhere"4 on her parents' bookshelf to Laurel Ulrich's "Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History"5, a declaration of female rebellious spirit, in her research deck; from the historical and cultural regulation of ideal female roles—Amazonian warriors needing to cut off a breast, colonial—era witch hunts punishing rebellious women, to the early American concept of "Republican Motherhood." Not surprisingly, Wonder Woman, during the 1950s, was depowered to be office secretary, an attempt to make her more relatable. While translating works like Joan Didion in “The Paris Review,”6 she reflected on the typical images of male writers like Hemingway—dashing, reckless, fearless—while female writers had to create in secrecy. Writing for women was seen as rebellious; being oneself was even a luxury. Women were expected to sacrifice themselves to meet societal expectations but were not allowed to be themselves.

left, image above: image still, The Wizard of Oz, 1939

left, image below: image still, The Simpsons, Treehouse of Horror XIX [S20E04], 2008

right: Julia Long, Are You a Bad Witch or a Good Witch, watercolour on paper, 76 x 56 cm, 2024

left, image below: image still, The Simpsons, Treehouse of Horror XIX [S20E04], 2008

right: Julia Long, Are You a Bad Witch or a Good Witch, watercolour on paper, 76 x 56 cm, 2024

The climax of this section and indeed the entire exhibition is the painting "Mirror of the Times." This piece draws inspiration from an old mirror in a friend's colonial mansion in Shanghai, reflecting three female figures: Julia Long’s great-grandmother, who was an artist before becoming a mother and ultimately chose marriage; her grandmother, who followed her husband's lead in life, resulting in various disappointments; and Miss Wang from "Blossoms,"7 written by Jin Yucheng, representing the current generation of women who can choose for themselves and become their own anchors.

Julia Long, The Mirror of Times, 76 x 56 cm, watercolour on paper, 2024

From New York City to Beijing, Julia Long constructs an ever-expanding universe focused on gender issues, forming a more systematic body of discursive works. The new series on view, her ongoing artistic practice, research, translations, original writings, and numerous cross-disciplinary collaborations continuously explore gender roles, transcultural narratives, and the complex interplay between individual choice and societal expectations. Through the gaze of various female characters in the exhibition, viewers can glimpse and imagine the interiors, delving further into this intricate discourse. This foundation supports progressive gender issues in social movements worldwide and serves as a tool to identify and call out potential regressions in these efforts.

Zong Han

June 9th, 2024

on the train from Munich, Germany to Basel, Switzerland

[1] Kate Bush, “Running Up That Hill,” on Hounds of Love, 1985.

[2] Brothers Grimm, “The Frog Prince,” in Grimm’s Fairy Tales, 1812.

[3] Zadie Smith, “Peonies,” in Intimations: Six Essays (New York: Penguin Books, 2020).

[4] Jana U. Ehrhardt, Good Girls Go to Heaven, Bad Girls Go Everywhere (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997).

[5] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History (New York: Vintage, 2008).

[6] Joan Didion, “The Art of Fiction No.71,” interviewed by Linda Kuehl, The Paris Review, no.74 (Fall-Winter 1978).

[7] Jin Yucheng, Blossoms (Shanghai literature and Art Publishing House, 2012). Blossoms is intricate portrayal of Shanghai’s social and cultural transformation from the 1960s to the 1990s, woven through the lives of various interconnected characters.

About the Writer

Zong HAN is a culture strategist, advisor and writer based in Singapore.

About the Artist

Julia (Di) Long (b.1984, China) is an artist currently working and living in Beijing China. Born in a family of three generations’ practice in arts, she has chosen a discursive path that later led her way to the art world. Long earned her bachelor degree with highest honor in world history from Nankai University in Tianjin China, furthered her study in American history and gender history in University of Georgia with a full scholarship. She then moved to New York and worked as a restaurant publicist, while making art, doing illustration for magazines, translating articles, and hosting a podcast.

Long has shifted her focus mainly on art in 2017, since then she has done three solo exhibitions at Tabula Rasa Gallery Beijing, along with her translation works of female writers and her writings with a gender focus, she has thus formatted her discursive themes of artistic endeavors into a universe focusing on the discussion on feminism, women’s history and experiences, with an intercultural perspective based on her academic background and personal observation.

Selected solo exhibitions include: If We Could Swap Our Places, with Tabula Rasa Gallery & Bao Collection Space (Upcoming, Shanghai 2024); Running Up That Hill, Tabula Rasa Gallery(London 2024), Provisional Emotions, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2021); Meanwhile, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2019); One Eighth of the Narrative, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2017); Serendipity, UNdefine (Shanghai, 2014); Selected group shows include: Home Sweet Home, Power Station of Art (Shanghai 2017); Nián Nián :The Power and Agency of Animal Forms, (Deji Museum, 2023).

Publication: Distracted, an essay collection (Guangxi Normal University Press, 2021) Selected translation publication include: Joan Didion’s two Paris Review interviews ( The Art of Fiction No.71, and The Art of Non-fiction No. 1) ; Hilary Mantel, Paris Review interview ( The Art of Fiction, No. 226), Chinese version published in 2020. Patti Smith, Devotion( Why I Write), (Yale University Press, 2017), Chinese version published in 2021.

Tabula Rasa Gallery (London)

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Tuesday - Saturday 12:00 - 18:00 | Sunday - Monday Closed

© 2022 Tabula Rasa Gallery