INTERVIEW:

Kristy M. Chan: Between two Narratives

by ArtPDF

The interview was originally published in Mandarin and was translated into English by Tabula Rasa Gallery.

Kristy M. Chan: Between two Narratives

by ArtPDF

The interview was originally published in Mandarin and was translated into English by Tabula Rasa Gallery.

Kristy M Chan: Between two Narratives

Interview by ArtPDF, 7 January 2026, 17:52, Shanghai

![]()

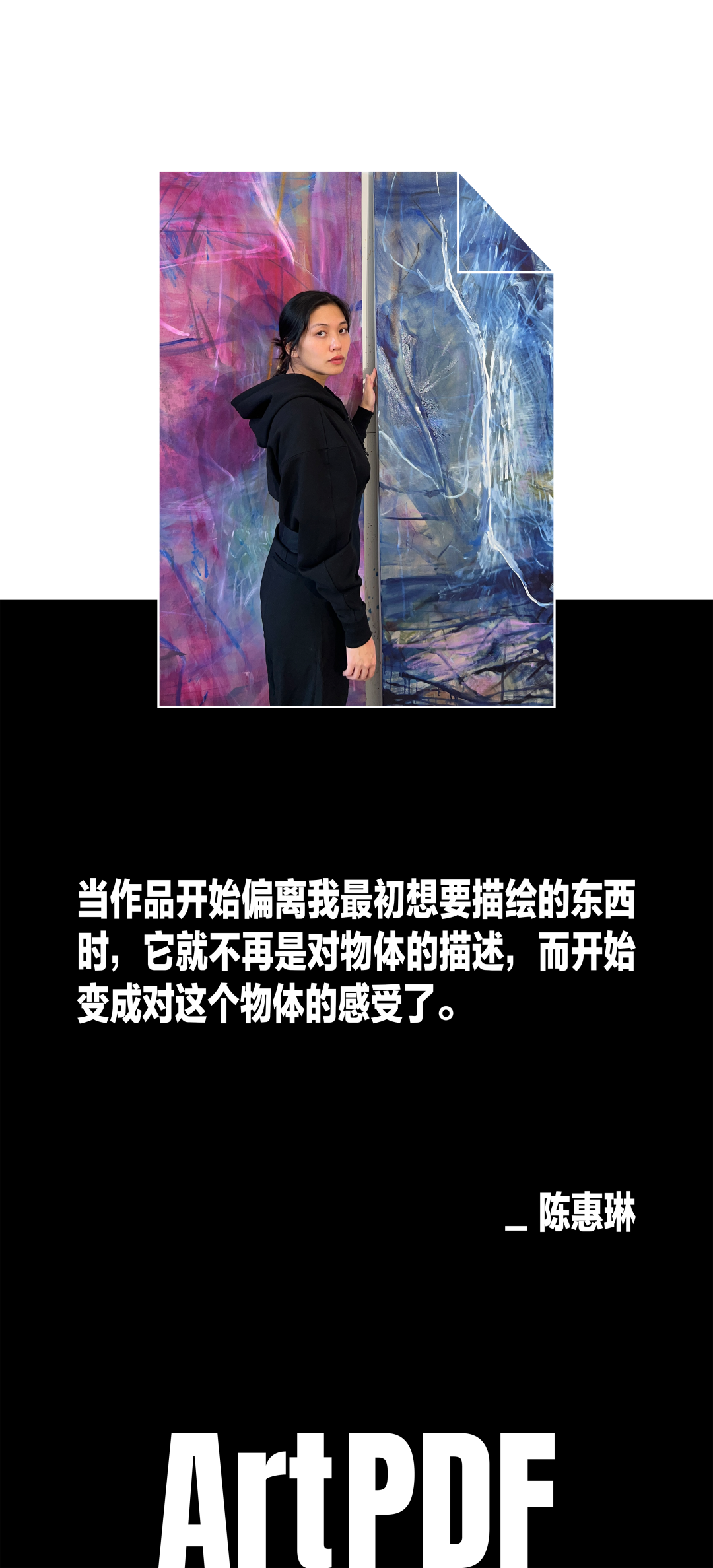

“When my work starts to alter from the original intention, it stops to retain its purpose as a physical entity, but moreover starts to be a personal perception towards the object itself.“

Although Kristy M Chan has always been cautious about labels, in today’s artistic context she is almost inevitably perceived as a post-’95 female abstract painter with multicultural experiences who has long worked within international systems. It is precisely this seemingly clear yet potentially unstable identity framework that allows her work to create deviations and surprises even before expectations are formed—this is also why we decided to conduct this interview.

During our conversation, Kristy M Chan had returned to Hong Kong. From this “priceless, densely packed” city to London, her painting practice begins with an active acceptance of real conditions: cramped studios, constantly changing residences, limited ready-to-hand materials, a rhythmic working routine, and the creative experience derived from these dual contexts.

![]()

Hi Kristy! Where are you right now?

How do you usually organize your outdoor painting sessions? Where do you go, and what do you paint?

Do you work on small studies at home?

Do you have a studio in London?

I spend most of my time in London, which is where my main studio is. It’s actually quite tidy. Given the scale of my works, the space isn’t large, but it’s organized in its disorder. Mostly, it’s full of materials—tubes of paint everywhere, lots of rags and gloves. I always wear gloves when painting.

How large is your studio?

![]()

![]()

How do you approach painting large-scale works?

When creating a series of works, how do you plan and progress, especially with limited studio space?

Do you decide on each work’s concept and size before starting a series?

![]()

20 Metres, Oil on linen, 180×190 cm, 2025

![]()

Culprit, Oil on linen, 70×90 cm, 2025

This method seems more rational and planned than one might imagine your creative process to be.

Many of your works come from travel and interactions with friends. How do you record your ideas, and do you bring them back to the studio?

Can you give an example of a work and how it reflects your initial thoughts or experiences?

![]()

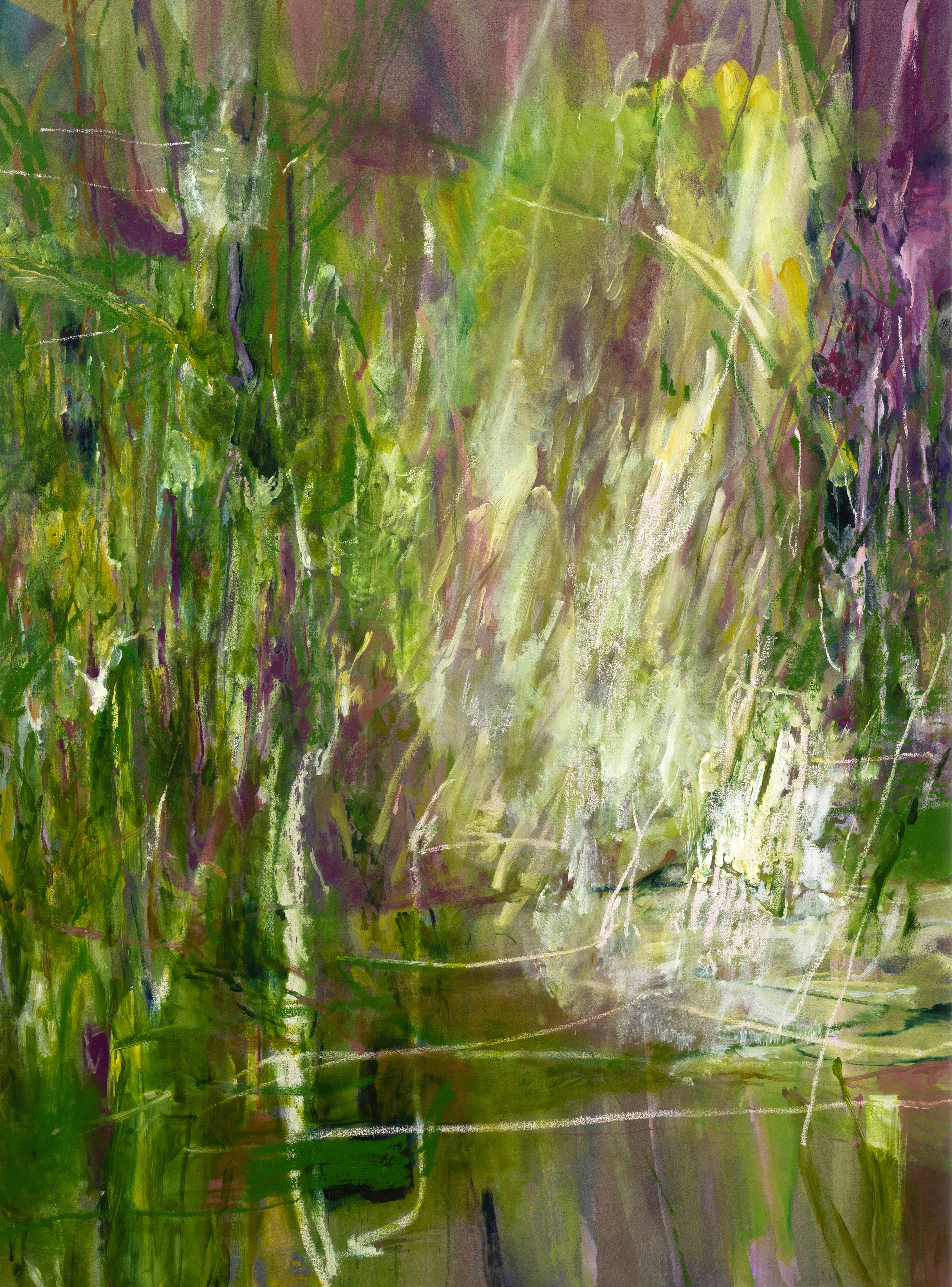

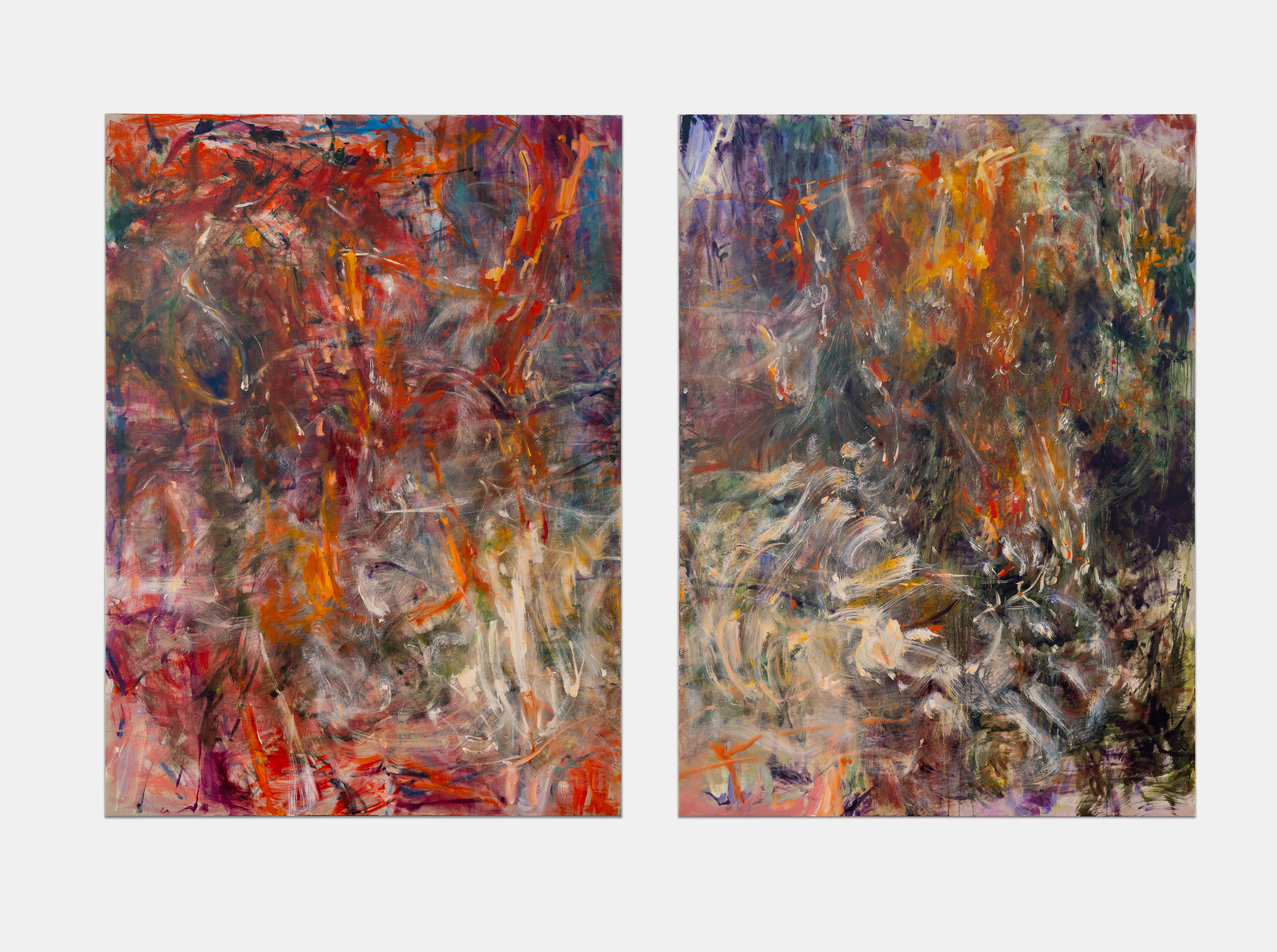

Woodland Almanac,Oil on linen, 190×140 cm (each), 2024–2025

![]()

Draba, Oil on linen, 200×170 cm, 2024–2025

When inspiration strikes, do you take photos or write notes to capture the moment?

You mentioned writing down words as notes. Are they bullet points or more diary-like descriptions?

![]()

Fragments of ideas recorded in Kristy M. Chan’s notes

Have you painted works about the fire?

How do you translate such immediate feelings into a work’s structure?

How does the shift from describing an object to feeling it happen in your process?

![]()

Self-sabotage (Schadenfreude), Oil on linen, 200×169 cm, 2024

![]()

Insects Singing, Oil on linen, 200×148 cm, 2024

Are your lines more traces of your psychological or physical state, or consciously placed formal elements?

When deciding whether to use large or small canvases, how do you choose which ideas go where?

Did your childhood training, like ikebana, influence your work intuitively or consciously?

![]()

Aqua Regia. Oil on linen, 190×280 cm, 2024

How did you start learning ikebana?

By the way, do your works involve any elements of metaphysics or esotericism?

In Hong Kong, people take these beliefs seriously. Have you studied their principles?

![]()

签, Oil on linen, 70×150 cm, 2025

Your works usually have both English and Chinese titles. English titles are often more conceptual, psychological, or philosophical, while Chinese titles are more poetic and grounded in everyday imagination. How do the two languages influence your thinking? How do they affect the audience’s understanding of your work?

How do these two languages relate to your visual composition? Do the language of the titles affect how you structure or arrange your work?

When you exhibit your works in the UK without Chinese titles, does that mean you are not emphasizing your multicultural background?

![]()

River of Wells, Oil on linen and Rolling Paper, 200×170x5 cm, 2024

Do you hope viewers will see your works and concepts as part of their own culture?

I see. Do you intentionally create some difference or slight dissonance between the Chinese and English titles?

You often use purple, red, and black, which carry strong psychological symbolism. How do you decide on color in your work?

![]()

You Don’t Have To Be Lonely, It’s All In Your Head, Oil on linen, 150×150 cm, 2023

You mentioned wanting to avoid academic painting styles—choosing colors randomly, is that to avoid being constrained?

When did you decide not to follow the academic style?

How do you specifically avoid the academic style?

![]()

Hippocampus, 2024, Oil on linen, 170×200 cm

From the outside, people might label your work as abstract or conceptual. What kind of artist would you least like to be mistaken for?

Haha, why?

Editor-in-Chief | Paco

Compiled by | Yu Mingyi

Images | Artist, Tabula Rasa Gallery, and ArtPDF Database

Download PDF

About the Artist

Kristy M Chan (b. 1997, Hong Kong) lives and works in London. Chan creates artworks that traverse between figuration and abstraction, resulting in energetic, intuitive, and autobiographical compositions. Departing from surreal and bewildering moments in contemporary life, Chan describes her works as 'stolen realities.' Primarily employing densely applied oil and oil stick, her paintings serve as visual archives of intense personal interactions amid the transient dynamism of the city. Living between Hong Kong and London, Chan incorporates subject matters from an outsider's perspective, contemplating the interplay between her identity influenced by both Eastern and Western cultures. Chan is intrigued by extracting descriptive metaphors from literature and reimagining them in her own unique way.

Kristy M. Chan completed her BFA at UCL Slade School of Fine Art in 2019 and her MA in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. Her recent solo exhibitions include: Night Studio, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2024); Molehill Mountaineer, The Cabin (Los Angeles, 2023); Binge, The Artist Room and Simon Lee Gallery (London, 2022); Strong Cookie, Prior Art Space (Berlin, 2022); Totally Not, The Artist Room (London, 2021).

Selected recent group exhibitions include: Nov. 10 2001, ZiWU Gallery (Shanghai, 2025); Up Close, MINT Gallery (Munich, 2025); Strings Attached, Pipeline Contemporary (London, 2025); IMMATERIAL, Soho Revue, (London, 2025);Abstraction (Re) Creation -20 under 40, X Museum, (Beijing, 2025); The Cloud Catcher, Perrotin (Shanghai, 2025); Untalely, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2023); Bordercrossing, Yuz Museum (Shanghai, 2023); Women in Abstraction, What’s Up/Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 2023); Immersed, curated by Jack Siebert, (Los Angeles, 2023); Lightness of Being, KWAI FUNG HIN (Hong Kong, 2023); Tabula Rasa: Unveiled, No.9 Cork Street (London, 2023); The Sky Above the Roof, Tabula Rasa, Beijing (2022); Märchen Brunnen, Haus der Statistik (Berlin, 2022); An Arcadian Kind of Love, Soho Revue (London, 2022); New Romantics, The Artist Room x Phillips, Lee Eugean Gallery (Seoul, 2022); Femme-Ate, Soho Revue, London (2021); Big Soft Illusion, Alte Handelsschule, Leipzig (2020); Haam4 Seoi2 Goeng1, Hong Kong Visual Art Centre, Hong Kong (2019).

Chan has also undertaken residencies at Dragon Hill Residence, Mouans-Sartoux, France (2024); Beecher Residency, Connecticut (2023); The Cabin, Los Angeles (2022–2023); Del Arco Residency, Berlin (2022); PILOTENKUECHE, Leipzig (2020); and AiR Frosterus, Finland (2019).

Her works are included in significant private and public collections, including: Danjuma Collection, London; Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins, Mougins, France; Forbes China, Shanghai; Zabludowicz Collection, London; X Museum, Beijing.

Interview by ArtPDF, 7 January 2026, 17:52, Shanghai

“When my work starts to alter from the original intention, it stops to retain its purpose as a physical entity, but moreover starts to be a personal perception towards the object itself.“

Although Kristy M Chan has always been cautious about labels, in today’s artistic context she is almost inevitably perceived as a post-’95 female abstract painter with multicultural experiences who has long worked within international systems. It is precisely this seemingly clear yet potentially unstable identity framework that allows her work to create deviations and surprises even before expectations are formed—this is also why we decided to conduct this interview.

During our conversation, Kristy M Chan had returned to Hong Kong. From this “priceless, densely packed” city to London, her painting practice begins with an active acceptance of real conditions: cramped studios, constantly changing residences, limited ready-to-hand materials, a rhythmic working routine, and the creative experience derived from these dual contexts.

A Flame's Shadow, Oil on linen, 200×149 cm, 2024

Hi Kristy! Where are you right now?

At home. I actually don’t have a studio in Hong Kong, so I mostly create outdoors. A few years ago, I prepared some canvases and kept them in storage, ready to use when needed.

How do you usually organize your outdoor painting sessions? Where do you go, and what do you paint?

I paint in the air-conditioned room where my late dog used to stay, or I carry small painting tools while hiking. I also go to quiet ponds near Hong Kong. When painting outside, I only bring lightly primed paper, oil pastels, and pencils.

Do you work on small studies at home?

I’m not the type to make sketches. I treat small works as complete pieces in themselves, not as preparatory drafts. My creative process is very intuitive. If I do make a sketch for a work, it’s usually just rough combinations of shapes—and I don’t think they ever really translate directly into the finished work.

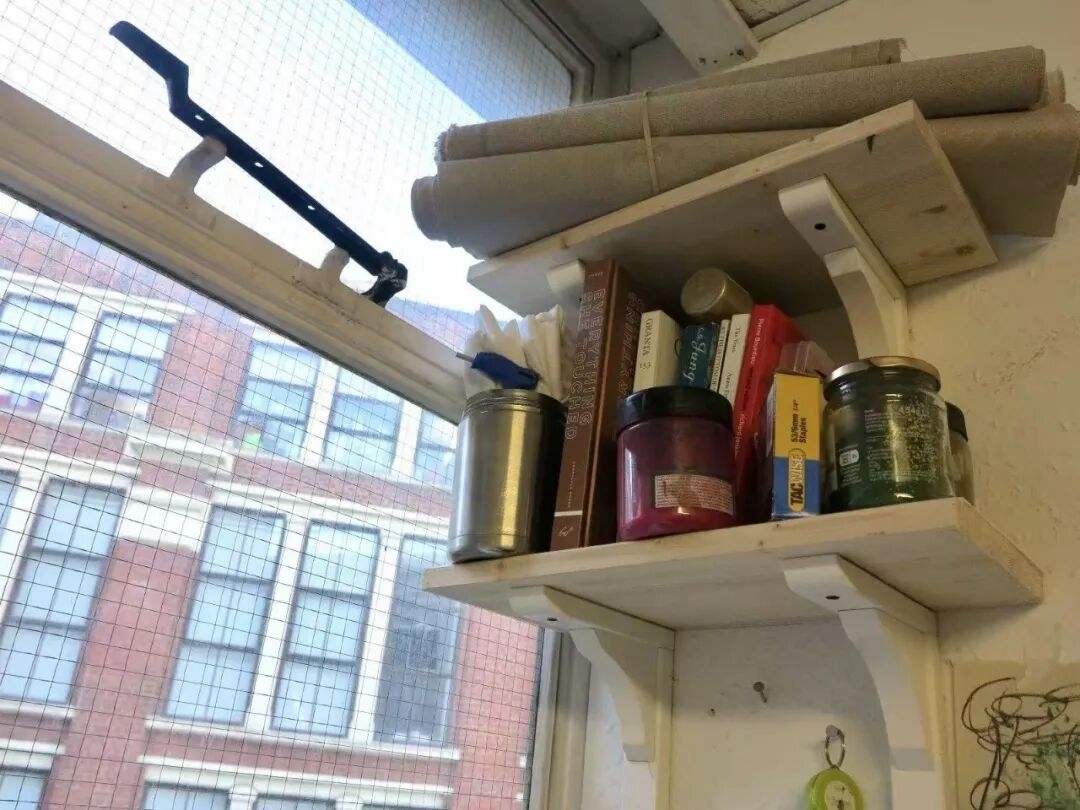

Do you have a studio in London?

I spend most of my time in London, which is where my main studio is. It’s actually quite tidy. Given the scale of my works, the space isn’t large, but it’s organized in its disorder. Mostly, it’s full of materials—tubes of paint everywhere, lots of rags and gloves. I always wear gloves when painting.

How large is your studio?

9 square meters. I know—it’s really small, haha. I started renting it last March on a one-year lease; later, I’ll probably find a slightly larger space.

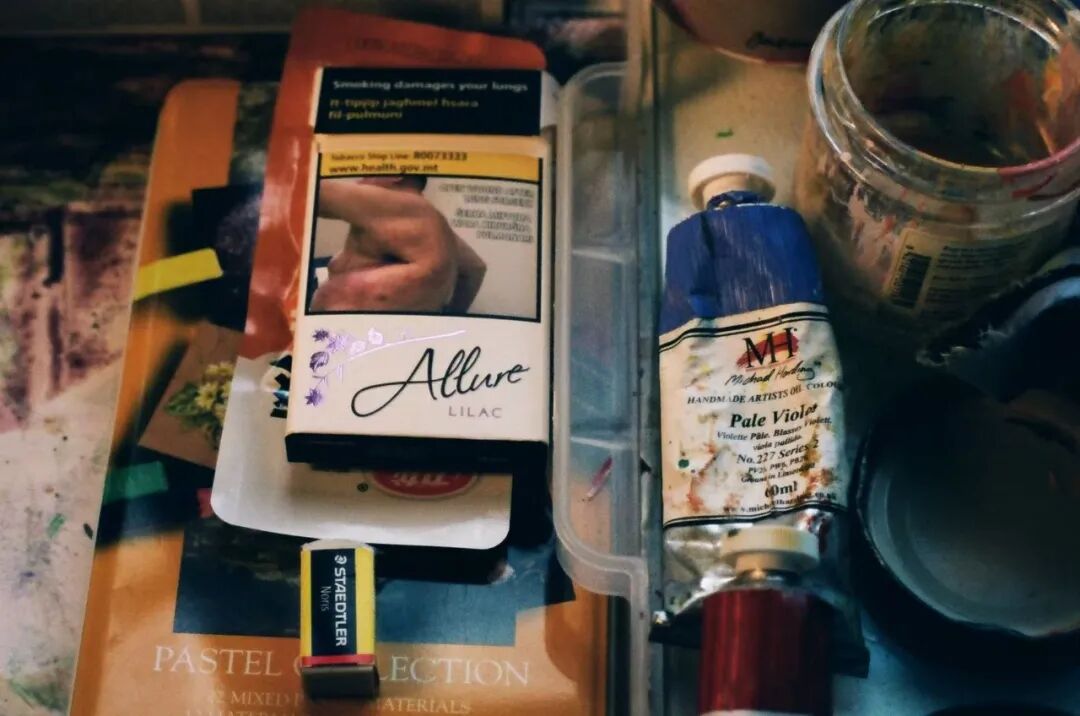

Kristy’s Studio in London

How do you approach painting large-scale works?

I think fully utilizing the space is important, and I really enjoy that.

Since I started painting in 2016, I haven’t had a fixed studio. Most of the time, I painted in my living room, and I rented a studio for a while later. I like moving a lot—in London, I move almost every year. Every time I move, I look for a new studio, and being able to use every inch of the space makes me very happy. In a way, Hong Kong’s “land-for-gold” concept has always influenced me.

Since I started painting in 2016, I haven’t had a fixed studio. Most of the time, I painted in my living room, and I rented a studio for a while later. I like moving a lot—in London, I move almost every year. Every time I move, I look for a new studio, and being able to use every inch of the space makes me very happy. In a way, Hong Kong’s “land-for-gold” concept has always influenced me.

When creating a series of works, how do you plan and progress, especially with limited studio space?

I usually work on one or two paintings at a time, sometimes alongside smaller pieces. At the end of the day, I turn the paintings away and don’t look at them until it’s time to continue.

This approach works well for me. It’s like a rotation system, almost a “factory mode”: after working on a piece for a while, I put it on the “conveyor belt” and switch to the next. I might focus on one work for a week straight before moving on.

This approach works well for me. It’s like a rotation system, almost a “factory mode”: after working on a piece for a while, I put it on the “conveyor belt” and switch to the next. I might focus on one work for a week straight before moving on.

Do you decide on each work’s concept and size before starting a series?

Yes. I make a list to clarify all the sizes I want in the series. I also set reminders in my calendar to schedule production time for each piece. I can only start a new series after the previous works are completed and leave the studio; otherwise, they just sit there.

20 Metres, Oil on linen, 180×190 cm, 2025

Culprit, Oil on linen, 70×90 cm, 2025

This method seems more rational and planned than one might imagine your creative process to be.

My work mainly responds to nature and literature. When I bring emotions and feelings into the studio, a relatively restrained, low-distraction space is actually helpful. I consider myself practical and work at a fairly fast pace in the studio.

Many of your works come from travel and interactions with friends. How do you record your ideas, and do you bring them back to the studio?

I’m not entirely sure. When I paint, my attention is almost entirely on the painting itself—I don’t think about other things or emotions. The process is mostly driven by what I see in the moment. I feel painting is one of the most immediately rewarding art forms; once the brush touches the canvas, I see a result and can respond to it right away.

For me, this drives creation. True reflection usually comes after finishing a work—once I step back and look again, insights appear. My works often take two to three months, sometimes longer, to complete.

Revisiting these works, I sometimes realize that what I was thinking at that moment is reflected in them. I also note important events, quotes, or fragments of text. Looking back at these notes, I often see how they resonate with what I’ve tried to capture in my paintings.

For me, this drives creation. True reflection usually comes after finishing a work—once I step back and look again, insights appear. My works often take two to three months, sometimes longer, to complete.

Revisiting these works, I sometimes realize that what I was thinking at that moment is reflected in them. I also note important events, quotes, or fragments of text. Looking back at these notes, I often see how they resonate with what I’ve tried to capture in my paintings.

Can you give an example of a work and how it reflects your initial thoughts or experiences?

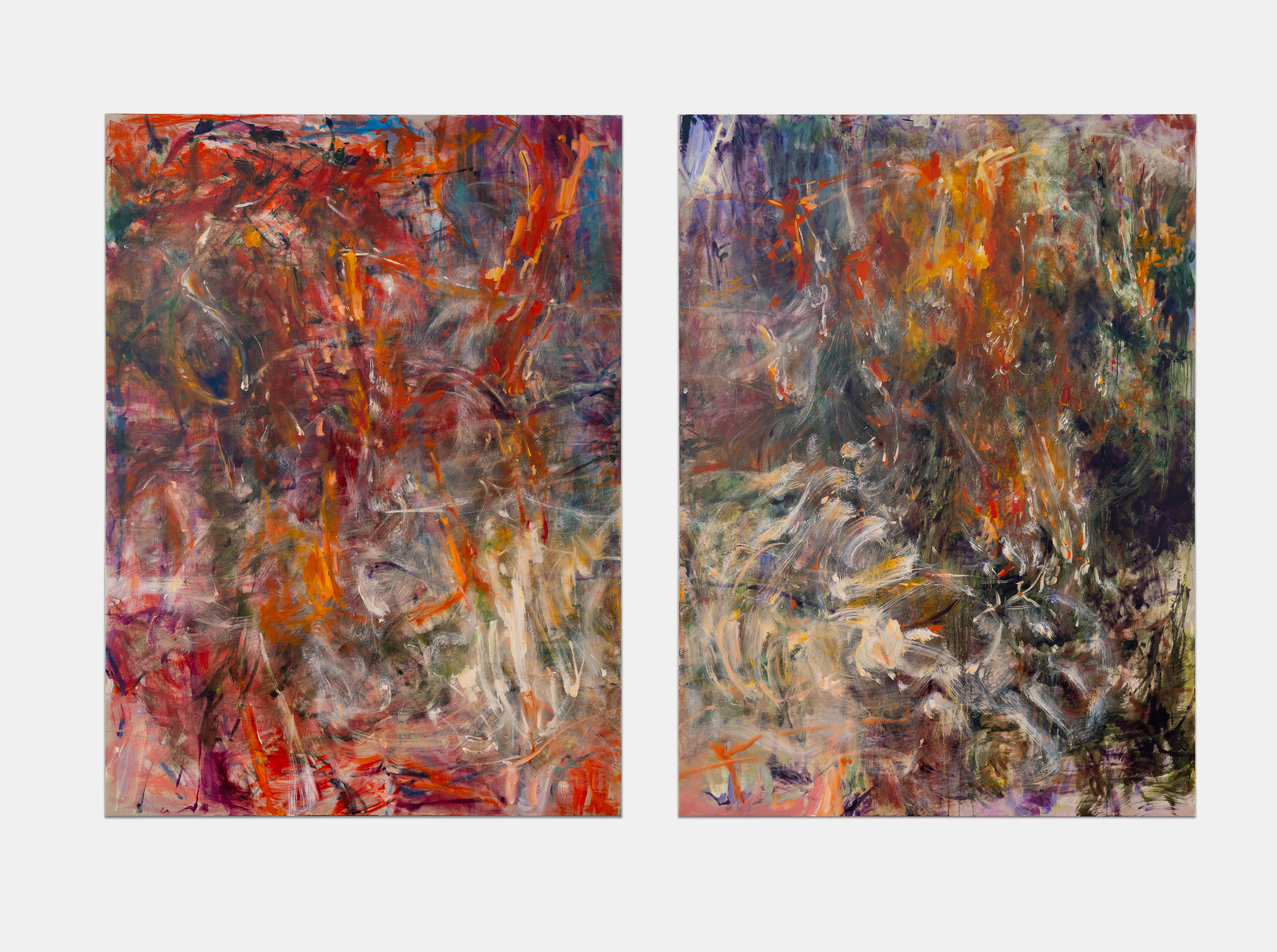

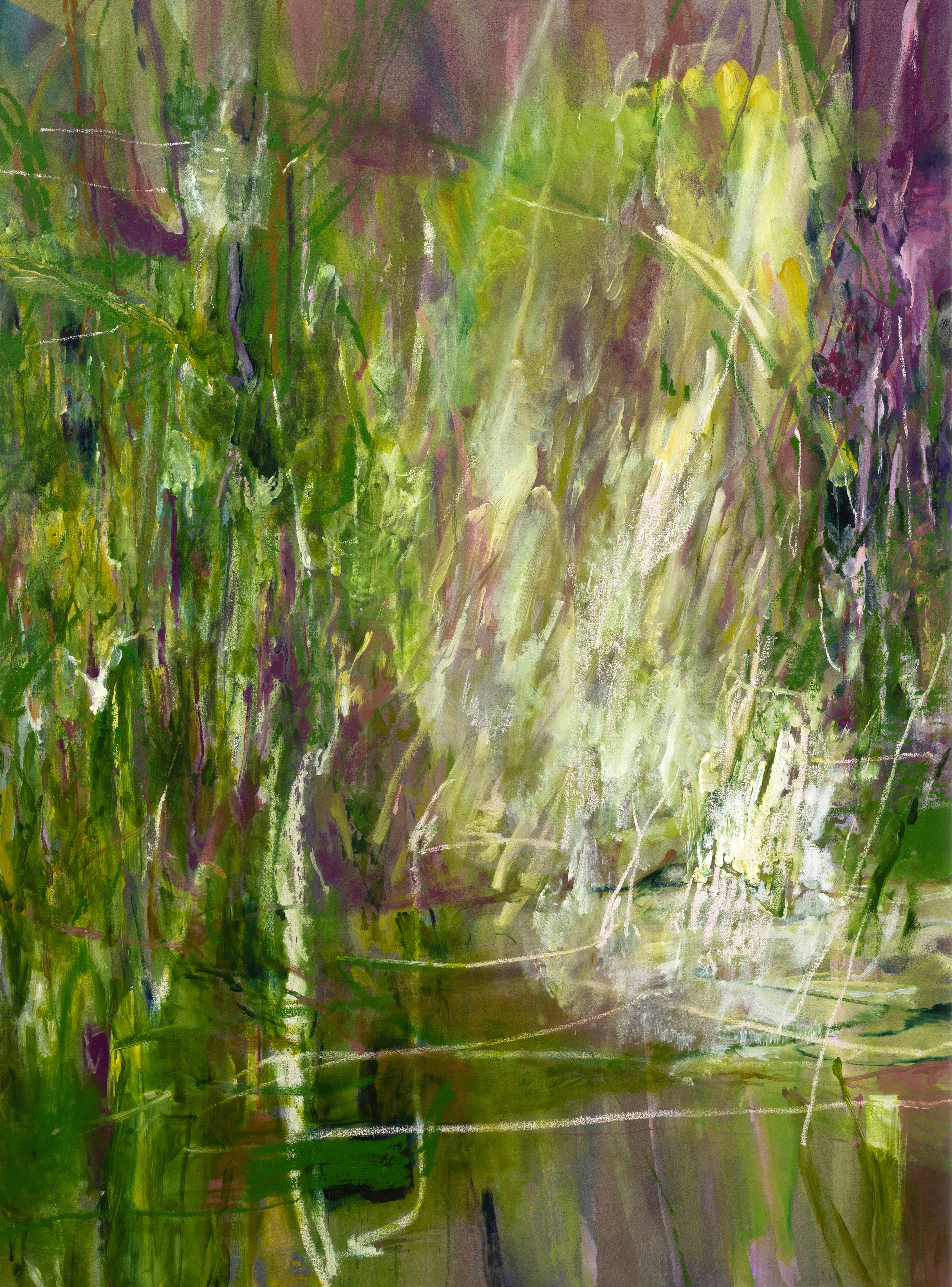

I started creating Woodland Almanac and Draba quite simply—I was watching a YouTuber making miniature scene models. She mentioned a book called Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold, which discusses philosophy, land ethics, and geopolitics, particularly how humans should responsibly relate to nature.

A few weeks later, on my way to Columbia Flower Market in London, I saw a tree in the transitional colors of autumn—breathtakingly beautiful. It made me realize autumn is often overlooked. Just like how people and scientists have only recently started paying attention to the female hormonal cycle and its impact on health and performance.Against this backdrop, I started Woodland Almanac, inspired by my hikes and explorations in the Woodland Trust forests in the UK, also connecting to the concept of Chinese “almanacs,” such as yearly zodiac-based calendars.

Draba is more directly inspired by a short poem in Sand County Almanac, recounting Aldo Leopold discovering Draba, a small, insignificant flower symbolizing the start of spring. It reminded me how tiny things can bring immense joy. This connects to small daily rituals in Chinese culture, like bathing with pomelo leaves or eating shrimp as a symbol of happiness—these tiny acts make life feel special.

A few weeks later, on my way to Columbia Flower Market in London, I saw a tree in the transitional colors of autumn—breathtakingly beautiful. It made me realize autumn is often overlooked. Just like how people and scientists have only recently started paying attention to the female hormonal cycle and its impact on health and performance.Against this backdrop, I started Woodland Almanac, inspired by my hikes and explorations in the Woodland Trust forests in the UK, also connecting to the concept of Chinese “almanacs,” such as yearly zodiac-based calendars.

Draba is more directly inspired by a short poem in Sand County Almanac, recounting Aldo Leopold discovering Draba, a small, insignificant flower symbolizing the start of spring. It reminded me how tiny things can bring immense joy. This connects to small daily rituals in Chinese culture, like bathing with pomelo leaves or eating shrimp as a symbol of happiness—these tiny acts make life feel special.

Woodland Almanac,Oil on linen, 190×140 cm (each), 2024–2025

Draba, Oil on linen, 200×170 cm, 2024–2025

When inspiration strikes, do you take photos or write notes to capture the moment?

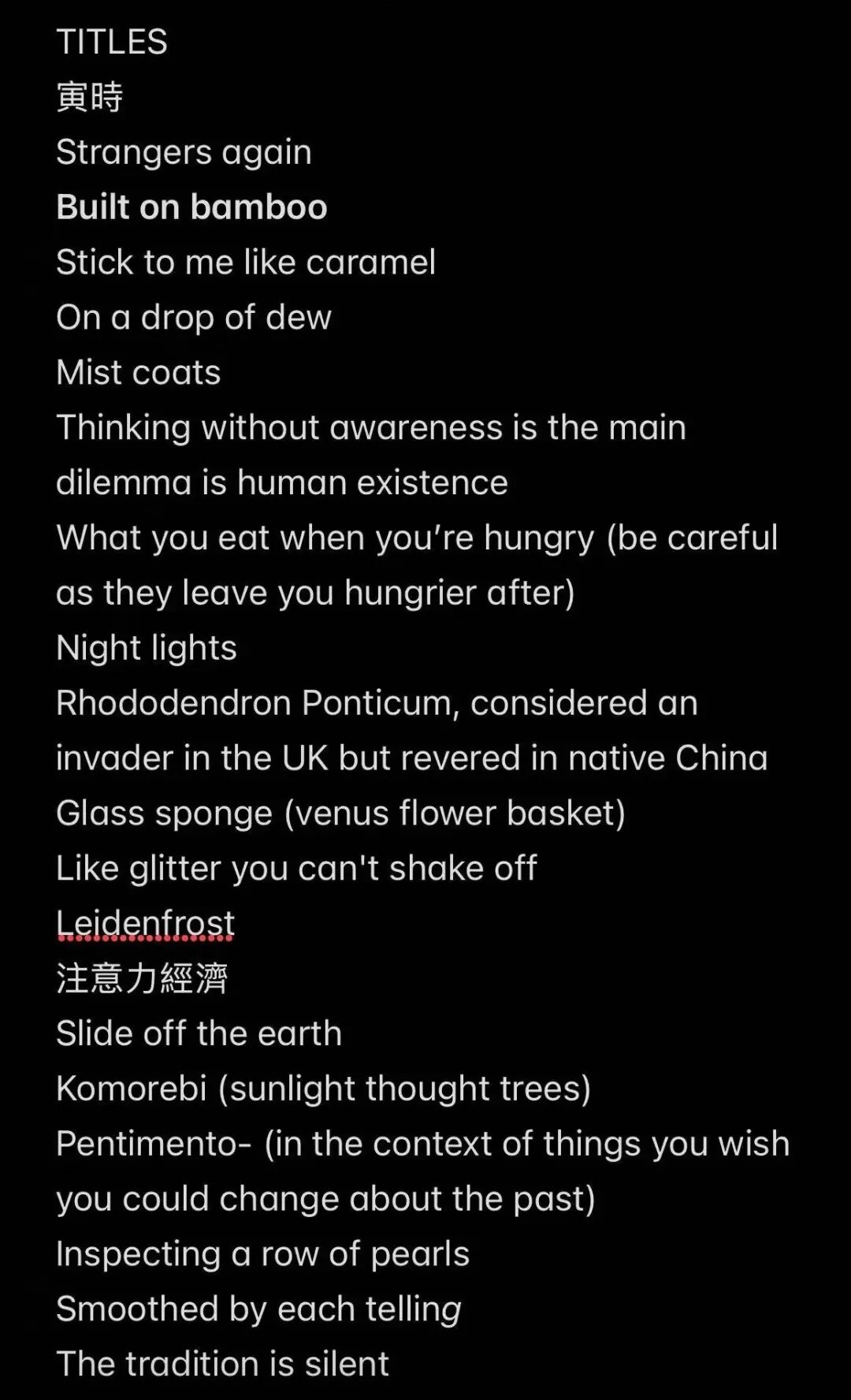

I don’t rely on visual cues, so I don’t photograph scenes I want to paint. Instead, I record language—words or short phrases I want to capture. They’re usually layered, sometimes personal, sometimes pointing to multiple meanings. Without context, viewers may not directly understand the work. It may sound cliché, but painting isn’t about answering questions—it’s about asking more. I once tried to be an academic painter, making everything “correct,” matching colors perfectly. But that killed the joy of expression and the pure pleasure of painting. Now I try not to rely on any reference framework.

You mentioned writing down words as notes. Are they bullet points or more diary-like descriptions?

Neither—more like fragments. For example, during a fire in Hong Kong, I thought about how bamboo scaffolding is such a fundamental part of Asian architecture. Some notes are about direct observations, like “bamboo,” while others are more casual, about food or hunger. One note I see now says: “Be careful, this will make you hungrier.”

Fragments of ideas recorded in Kristy M. Chan’s notes

Have you painted works about the fire?

Not yet—I feel painting that would make me uncomfortable.

How do you translate such immediate feelings into a work’s structure?

If I’m only thinking about bamboo, not the fire, I might start with very straight lines. I often use leftover paint from a previous work to sketch bamboo lines—straight and orderly—and build from there.

Of course, I inevitably “make mistakes,” like lines not being perfectly straight. That’s when the work becomes interesting. It starts to deviate—not from reality, but from my initial intention. It becomes less about describing objects and more about feeling them.

Of course, I inevitably “make mistakes,” like lines not being perfectly straight. That’s when the work becomes interesting. It starts to deviate—not from reality, but from my initial intention. It becomes less about describing objects and more about feeling them.

How does the shift from describing an object to feeling it happen in your process?

It happens when I focus entirely on painting itself—a mix of the known and unknown.

Most of the time, you don’t fully know what you’re doing, and that’s the charm of painting, especially abstract work. You embrace something undefinable; you can’t name it, but you feel if it’s “right.”

Most of the time, you don’t fully know what you’re doing, and that’s the charm of painting, especially abstract work. You embrace something undefinable; you can’t name it, but you feel if it’s “right.”

Self-sabotage (Schadenfreude), Oil on linen, 200×169 cm, 2024

Insects Singing, Oil on linen, 200×148 cm, 2024

Are your lines more traces of your psychological or physical state, or consciously placed formal elements?

They’re more autobiographical—personal and psychological, with a physical aspect. My body limits how I move, even with broad gestures, so lines record my body and movement. They also record my feelings when going to the studio every other day—the mental state before entering and the process of putting things aside once inside. It’s very personal.

When deciding whether to use large or small canvases, how do you choose which ideas go where?

I’m not entirely sure. Even small works get the same intensity. They’re not less layered, both in paint and thought. Size often depends on what’s immediately available. If I have an idea and don’t want to stretch a new canvas, I use an already-prepared small canvas. It’s pragmatic and sometimes coincidental—I always work with what I have. I’ve even used cosmetics for small pieces when I didn’t have the right tools—like bronzer as paint. Ultimately, it’s all chemistry. This approach lets me work more relaxed, not taking things too seriously. Painting thrives in the in-between, between frustration and joy.

Did your childhood training, like ikebana, influence your work intuitively or consciously?

Absolutely. My strong sense of structure comes from ikebana, which taught me composition, negative space, and focal points. Sometimes I use it unconsciously, only realizing when I see the finished work.

Aqua Regia. Oil on linen, 190×280 cm, 2024

How did you start learning ikebana?

My mother started learning ikebana about fifteen years ago. She would bring home some really beautiful arrangements, and I loved flowers as a child, so I said I wanted to learn too. I was eight years old at the time, and the teacher thought I had an intuitive sense for placing the flowers correctly, so she took me on as a student. I went about once a week, continuing until I was sixteen, and then I went to study in the UK.

By the way, do your works involve any elements of metaphysics or esotericism?

Not yet. But this year, I plan to experiment with a new series, for example, based on the “Nine Fortunes of Li Huo,” and I hope it will be more reflective. I think this is the beauty of being able to create in two or even three languages: I can produce works that are closely connected to my own upbringing and experiences. I really want to find a way to build a series that lightly touches on the fascinating aspects of Chinese metaphysics. I am quite drawn to ideas about fate and everything related to it. Even though I am generally skeptical, many of these concepts feel incredibly real. To some extent, I think I do believe in them. For instance, we are now in the “Fire Cycle,” while the previous twenty years were the “Earth Cycle.” Art and AI are closely linked to the Fire Cycle—it actually makes sense in a curious way.I’ve been exposed to these ideas since I was a child. Every year, a feng shui master would come to my home, and we would change the carpet color annually. I find these things very fascinating, and I hope more people can understand them. They might serve as clues for next year’s creative direction.

In Hong Kong, people take these beliefs seriously. Have you studied their principles?

No, though my mother has been learning them. Personally, I’m not very interested in the mathematical or formulaic aspects. I also don’t follow feng shui rules strictly—arranging every object perfectly would feel rigid. I’m more drawn to the small details that catch my interest, or fragments of childhood memory. For example, my mother often warned me not to kick the six copper coins by the door—these tiny things are much more engaging to me. This time, I also drew a lot at the Wong Tai Sin Temple in Hong Kong. One of the sticks of divination I drew will become the title of a painting I’ll exhibit there. When viewers look at the painting, they can imagine themselves drawing lots too. But I won’t reveal which stick it is until 2027—by then, I’ll have transformed into “Master Chan,” helping people interpret the sticks, haha.

签, Oil on linen, 70×150 cm, 2025

Your works usually have both English and Chinese titles. English titles are often more conceptual, psychological, or philosophical, while Chinese titles are more poetic and grounded in everyday imagination. How do the two languages influence your thinking? How do they affect the audience’s understanding of your work?

I think it’s mainly because I left Hong Kong at sixteen, so my Chinese reflects that age. This is why my Chinese titles are more rooted in childhood or early experiences. I only really began identifying as an artist after going to the UK, so thinking in English feels more mature and complete. When I speak in Chinese or Cantonese, my father sometimes says I sound like a child. I think this reflects my psychological age in different languages. That said, I do try to express my art clearly in Chinese, because if I can’t explain my work in my mother tongue, I feel a little disappointed.

How do these two languages relate to your visual composition? Do the language of the titles affect how you structure or arrange your work?

At first, whenever an exhibition was held in Asia, I would give my works both Chinese and English titles. If the exhibition is only in Europe, like in the UK or the US, I usually don’t give a Chinese title—not because I don’t want to, but because of contextual considerations. Art often feels intimidating to those outside the art world. I didn’t grow up in the art scene, so I often felt distant from it. If the work is exhibited in China or Hong Kong, giving it a Chinese title makes it feel immediately more approachable. I want both myself and the audience to feel close to it. That’s how I decide whether to give a work a Chinese title. However, some works I made in 2022 about my relationship with my parents have very specific Chinese titles. These titles are deeply rooted in Cantonese, and someone who doesn’t understand Cantonese might not understand them at all.

When you exhibit your works in the UK without Chinese titles, does that mean you are not emphasizing your multicultural background?

No, I think my work has always been multicultural. From this perspective, when it is shown in Europe or English-speaking countries, I just want it not to feel alien. Ultimately, it’s about trying to build connections. I think almost everyone wants to connect in some way, and painting is one of those ways—an artist connects with themselves and, simultaneously, with others. I don’t want either myself or the audience to feel alienated.

River of Wells, Oil on linen and Rolling Paper, 200×170x5 cm, 2024

Do you hope viewers will see your works and concepts as part of their own culture?

It really depends on the viewer. I don’t want to impose any ideas; I just hope the work can be understood—not only what it means to me, but also how it can generate meaning for others.Outside China and the UK, I will naturally be seen as an outsider. But in a sense, I hope this cultural experience belongs to both them and me. I am also cautious about labels and prefer my work to remain in a gray area.

I see. Do you intentionally create some difference or slight dissonance between the Chinese and English titles?

Yes, I like to be a little playful. Someone who knows both languages can understand one meaning; someone who knows only one language can understand another. Usually, I complete the painting first, fully understand its theme, and then choose the most suitable title.

You often use purple, red, and black, which carry strong psychological symbolism. How do you decide on color in your work?

I like red and green. I’ve painted with blue, but it doesn’t move me as much. Now I’m experimenting with blue and brown. Mostly, it depends on what I have on hand—I don’t buy new paint unless I’ve completely used up the old. I like to make full use of existing materials, though red often dominates.

You Don’t Have To Be Lonely, It’s All In Your Head, Oil on linen, 150×150 cm, 2023

You mentioned wanting to avoid academic painting styles—choosing colors randomly, is that to avoid being constrained?

I don’t think so. Academic painting has certain rules, and I’ve seen people use very wild colors as a base, which is fine. I just find abstract painting makes me happier and allows me to express myself more fully.

When did you decide not to follow the academic style?

Around my second year at university in London. I started with figurative painting but realized that wasn’t what I truly wanted. Later, nobody in my class did very figurative academic painting.

How do you specifically avoid the academic style?

I don’t paint things that can be clearly named. Although I learned these as a child, I didn’t like rigid instruction. I sometimes paint figures or objects for practice, but that’s just exercise, not my real work. I once painted bicycles and people, which were meaningful to me then, but now it may be different; maybe I’ll paint them again in the future.

Hippocampus, 2024, Oil on linen, 170×200 cm

From the outside, people might label your work as abstract or conceptual. What kind of artist would you least like to be mistaken for?

I don’t care much about labels. People often say I’m an “Asian female abstract artist,” which is a bit stereotypical, but that’s okay. An artist just does their own thing; if people like it, that’s great. My favorite is when I say I’m a painter, and someone thinks I’m a “decorator.”

Haha, why?

In English, “painter” can mean both a fine artist and someone who paints walls. A “decorator” is someone who does interior decoration. I’ve always found this very funny—it’s almost a social metaphor and commentary in itself. One work I really like depicts two decorators in a gallery, painting walls every day for a month and a half. The work explores the relationship between so-called “high art” and labor. Works like this are very appealing to me because they make people rethink how art, work, and value are distinguished and defined.

Editor-in-Chief | Paco

Compiled by | Yu Mingyi

Images | Artist, Tabula Rasa Gallery, and ArtPDF Database

Download PDF

About the Artist

Kristy M Chan (b. 1997, Hong Kong) lives and works in London. Chan creates artworks that traverse between figuration and abstraction, resulting in energetic, intuitive, and autobiographical compositions. Departing from surreal and bewildering moments in contemporary life, Chan describes her works as 'stolen realities.' Primarily employing densely applied oil and oil stick, her paintings serve as visual archives of intense personal interactions amid the transient dynamism of the city. Living between Hong Kong and London, Chan incorporates subject matters from an outsider's perspective, contemplating the interplay between her identity influenced by both Eastern and Western cultures. Chan is intrigued by extracting descriptive metaphors from literature and reimagining them in her own unique way.

Kristy M. Chan completed her BFA at UCL Slade School of Fine Art in 2019 and her MA in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. Her recent solo exhibitions include: Night Studio, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2024); Molehill Mountaineer, The Cabin (Los Angeles, 2023); Binge, The Artist Room and Simon Lee Gallery (London, 2022); Strong Cookie, Prior Art Space (Berlin, 2022); Totally Not, The Artist Room (London, 2021).

Selected recent group exhibitions include: Nov. 10 2001, ZiWU Gallery (Shanghai, 2025); Up Close, MINT Gallery (Munich, 2025); Strings Attached, Pipeline Contemporary (London, 2025); IMMATERIAL, Soho Revue, (London, 2025);Abstraction (Re) Creation -20 under 40, X Museum, (Beijing, 2025); The Cloud Catcher, Perrotin (Shanghai, 2025); Untalely, Tabula Rasa Gallery (Beijing, 2023); Bordercrossing, Yuz Museum (Shanghai, 2023); Women in Abstraction, What’s Up/Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 2023); Immersed, curated by Jack Siebert, (Los Angeles, 2023); Lightness of Being, KWAI FUNG HIN (Hong Kong, 2023); Tabula Rasa: Unveiled, No.9 Cork Street (London, 2023); The Sky Above the Roof, Tabula Rasa, Beijing (2022); Märchen Brunnen, Haus der Statistik (Berlin, 2022); An Arcadian Kind of Love, Soho Revue (London, 2022); New Romantics, The Artist Room x Phillips, Lee Eugean Gallery (Seoul, 2022); Femme-Ate, Soho Revue, London (2021); Big Soft Illusion, Alte Handelsschule, Leipzig (2020); Haam4 Seoi2 Goeng1, Hong Kong Visual Art Centre, Hong Kong (2019).

Chan has also undertaken residencies at Dragon Hill Residence, Mouans-Sartoux, France (2024); Beecher Residency, Connecticut (2023); The Cabin, Los Angeles (2022–2023); Del Arco Residency, Berlin (2022); PILOTENKUECHE, Leipzig (2020); and AiR Frosterus, Finland (2019).

Her works are included in significant private and public collections, including: Danjuma Collection, London; Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins, Mougins, France; Forbes China, Shanghai; Zabludowicz Collection, London; X Museum, Beijing.

Tabula Rasa Gallery (London)

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Tuesday - Saturday 12:00 - 18:00 | Sunday - Monday Closed

© 2022 Tabula Rasa Gallery