Decoding Layers

Artists in Conversation between Katarina Caserman and Sophie Ruigrok

Hosted by curator, writer Vanessa Murrell

July 20, 2022

Tabula Rasa | London

Vanessa: Murrell (V): Thank you so much for coming to the artists talk “Decoding Layers”, where we will be decoding the layers of both of these artists' paintings. This artist talk is with two artists from this group show, Sophie Ruigrok and Katarina Caserman. They're both located in front of their works to make it easier for everyone to identify them. It's a group show with five very fresh, emerging female voices, and the other artists in the show are Shafei Xia, Cheri Smith and Anousha Payne, who are not here today. The title of the exhibition is “It's Better to be Cats than to be Loved”. It's quite an interesting title, quite lengthy. I guess the starting point of the title of the show, was this famous quote by Niccolò Machiavelli, which says, “it's better to be feared than to be loved”. Fear is like a motivator. Better than love. So that was like the starting point of the show. And of course, there's elements of the works that do include like cats.

Just to briefly introduce myself as well. My name is Vanessa Murrell. I'm a writer, curator and co-founder of the platform DATEAGLE Art. So, I perform like weekly studio visits and interviews with artists, usually not with that many audiences. It's usually an intimate just behind the scenes conversations. I'm really excited to be hosting this talk with these two amazing artists.

Sophie Ruigrok is a London-based artist who completed a postgraduate diploma in drawing at the Royal Drawing School in 2019. She was selected for the Bloomberg New Contemporaries in 2020. She has exhibited at the Sunday Painter at Marlborough, and at South London Gallery. Her practice is rich with archetypal symbolism, art historical reference, allusions to your(Sophie) personal life, and is also rooted in Jungian psychoanalysis, which is a term coined by Carl Jung, and I'm sure Sophie can tell us more about that in the talk.

Katarina Caserman, she's a London-based artist, originally from Slovenia. She graduated from a Master of Arts in Painting at the Royal College of Art this year, and she's got her Bachelor's Degree from the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana. So, your practice's aim is to give unseeable things, their material, their skeleton, their colour, shape, and their movements.

V: So, I guess that's a great starting point to my first question, which is, what are these unseeable things that you're trying to materialise?

Katarina Caserman (K): I always start off by saying that my work is an attempt to understand the transformative nature of things. I think that the word “attempt” is very important because when I talk about these unseeable things, it's just like we are getting closer and closer to representing the things that are constantly around us, but we cannot really see.

V: And those things, which seems kind of an abstract thing, is it like thoughts? Is it like memories? Is it dreams?

Sepraznazia

Katarina Caserman, 2022

40 x 34 cm, oil on linen

K: if you think of a memory or thoughts or time, these are the things that are present on our daily basic but the visibility is their inherent impossibility. They are constantly resisting representation. These things have a status of non-existence which means that it is technically impossible to imagine them in the first place. We know they're out there; we know they are part of our day-to-day life, but they cannot be put in any form, any visual form. It's just like, we're left with a term or definition, but not the visual aspect of those things.

V: That's really interesting. When I was talking with you about this work (Krhquyedro), you mentioned, it was quite subtle compared to other paintings that shout at you. And I thought this idea of shouting is very interesting. And maybe perhaps this piece that we're seeing here requires more attention, like more concentration into when looking at those different colours.

K: I usually use a lot of titanium white to bring back the light on the surface. In here, I didn't use it at all. So therefore, the layers are very much see through, you can still see the first layers. All the six or seven layers that I've done here, or even more, you can still see them. So, you have to stand in front of it and like move from side to side to actually perhaps grasp the whole painting. A very similar thing, I guess is what I did for when we had degree show: I had three small paintings and I placed them. One was very low; one was very high and one was like you can see it when you stand in front of it. So, I think that with small interventions like this, you can really see the painting differently because you have to put more effort than you usually would.

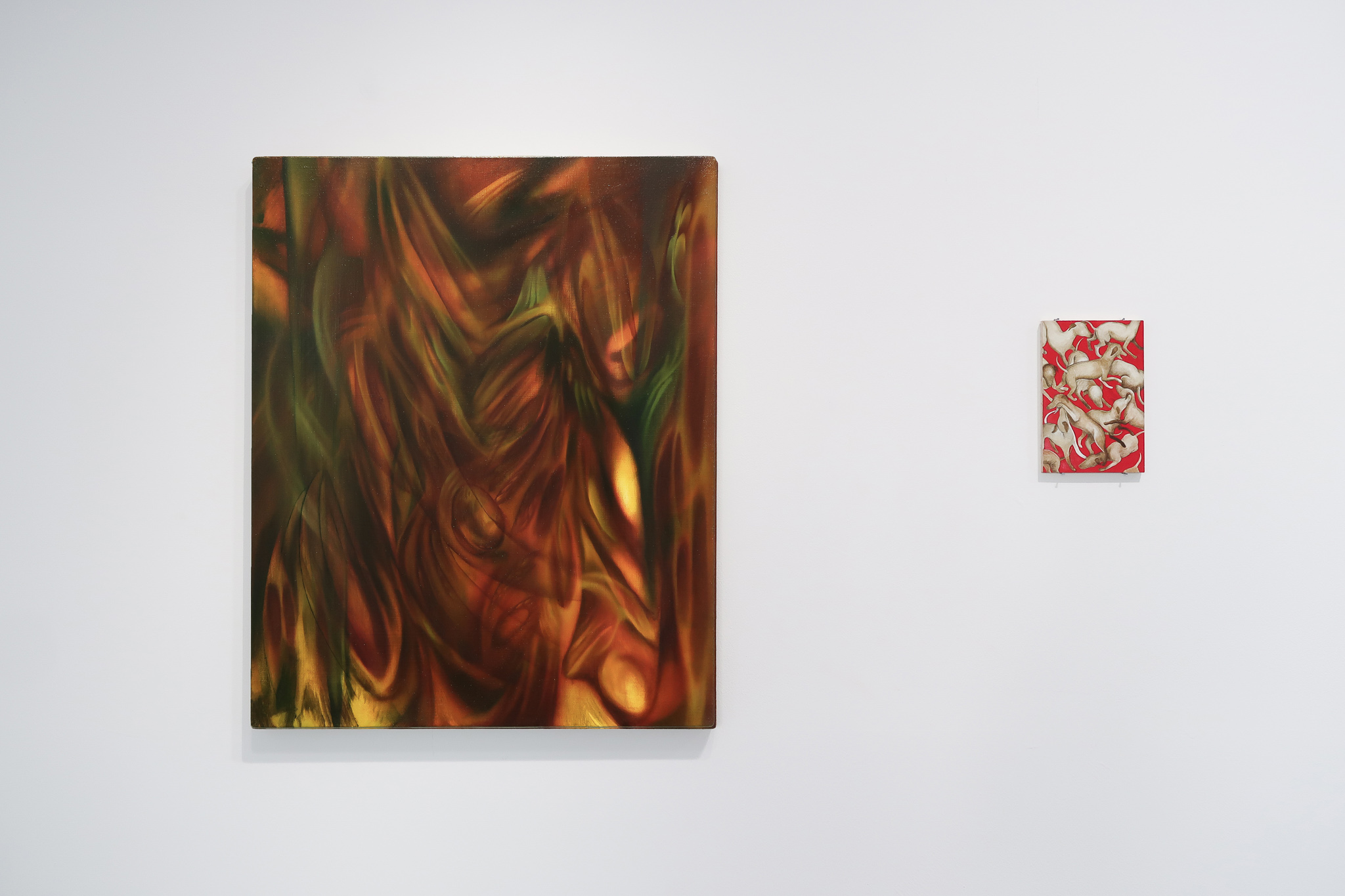

Installation view, RCA2022 Degree show of Katarina Caserman, Courtesy of the Artist and Julia Bennett Studio

K: Yeah, I mean, definitely. I don't want to say it is radically different from what I've done before, because it's still my work. I mean, before I was making paintings that were already very dynamic in composition. They had a lot of elements, the colours were very, very saturated, and I basically dissolved all the colours that I could. With this painting, in particular, I really wanted to make a painting that would require, as you said, more of the attention. So, it would require for the viewer and also for me to get closer to it, to look at it from different angles.I think there is an importance of paying more attention to the work itself, if you spend more time with a work then you perhaps can understand better as well.

Installatio view, Krhqoyedro (artwork left), 2022, 55 x 45 cm, oil on linen, at Tabula Rasa Gallery

V: I think it’s really interesting what you said that you do more than 10 layers, for specific work.The first layer is always visible, sort of like an X-Ray of your paintings where you can see the first layer, as so much of your work is about unseen things. It's creating these other elements of decoding or giving you like an X-Ray situation.

K: Yeah, I think that partially this one, like what I said at the beginning, I want to do a skeleton, I want to create a sort of the X-Ray effect. So, you get an insight of the structure, of the image, of the painting. But also, I want to leave the first layers, because they're crucial for what comes after. I think they are still a very important part of the whole painting, even if there's 10 layers in the end.

V: Moving to Sophie, I think when Katarina was talking about how she was curating the works in the degree show. Like high, low and all of these different elements, it reminded me of how you position works alongside each other. And particularly, in fact, in this hand, there is a complete close-up, and then other parts are like a blow-up of a hand. You play a lot with this perspective to create new meanings and relationships between things throught their position together? And is that something you consider quite a lot in your practice?

Sophie Ruigrok (S): Yeah, definitely. Often, it's not really planned before I start working, but it starts to happen as I'm working. I have a few dimensions I'm working on at the same time, and I think of the work as a network of images more than isolated images. In a way, this also introduces an idea of time into the work, as the viewer moves from piece to piece. There's not necessarily a specific, planned narrative that's happening, but you almost start to see the same scene from different angles. So here the mask is on this bed of velvet, and then it reappears in a hand. And then there’s the idea of the mask in the hand, which is then reversed to be a hand covering the face. And I suppose I want the viewer to start building links between the works and a personal narrative in their mind - this could even be on a subconscious level though. And then the work almost becomes a bit more cinematic in a way.

V: Moving to Sophie, I think when Katarina was talking about how she was curating the works in the degree show. Like high, low and all of these different elements, it reminded me of how you position works alongside each other. And particularly, in fact, in this hand, there is a complete close-up, and then other parts are like a blow-up of a hand. You play a lot with this perspective to create new meanings and relationships between things throught their position together? And is that something you consider quite a lot in your practice?

Sophie Ruigrok (S): Yeah, definitely. Often, it's not really planned before I start working, but it starts to happen as I'm working. I have a few dimensions I'm working on at the same time, and I think of the work as a network of images more than isolated images. In a way, this also introduces an idea of time into the work, as the viewer moves from piece to piece. There's not necessarily a specific, planned narrative that's happening, but you almost start to see the same scene from different angles. So here the mask is on this bed of velvet, and then it reappears in a hand. And then there’s the idea of the mask in the hand, which is then reversed to be a hand covering the face. And I suppose I want the viewer to start building links between the works and a personal narrative in their mind - this could even be on a subconscious level though. And then the work almost becomes a bit more cinematic in a way.

V: And what about the close-up? Because I know there was a reference of miniature you mentioned in our chat.

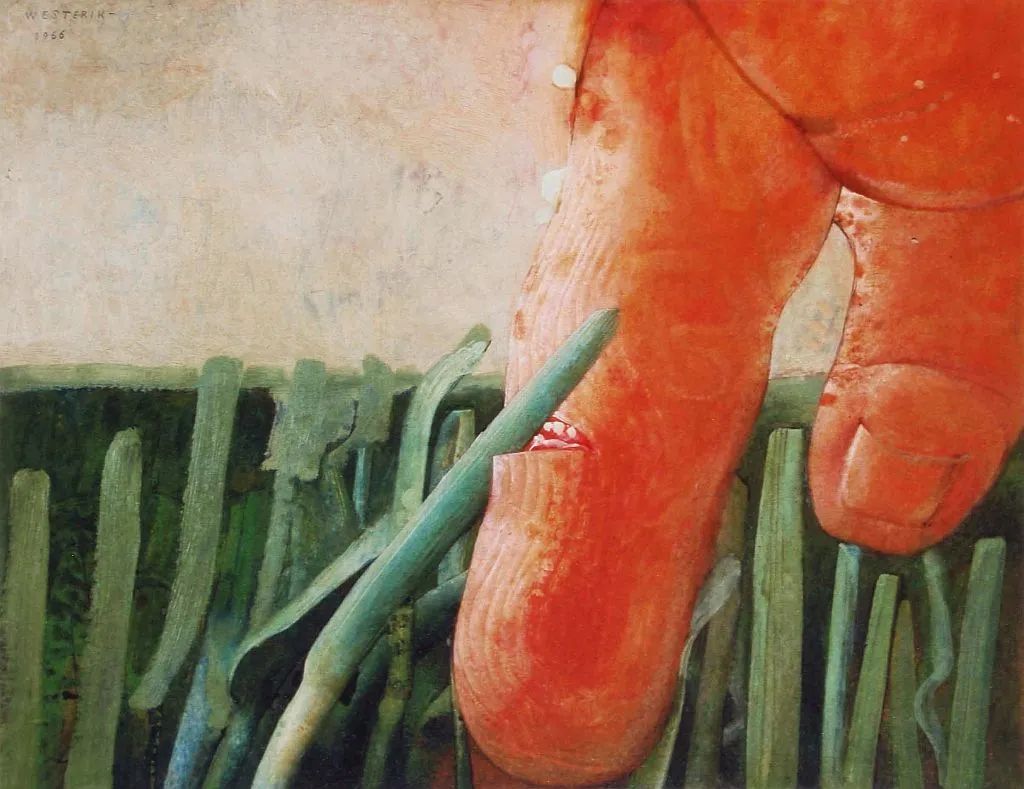

S: Yes, a few years ago, and my memory might not serve me particularly well, but I'll try my best. A book by a poet and philosopher called Susan Stewart, and the book is called On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir the Collection. She explores metaphors of the miniature and the giant as ways to look at many different aspects of culture. The book is very broad, but for her the miniature represents the interior world, like interiority, and the giant is something of the exterior world. That text had a massive influence on my visual language, and made me really think about zooming in super close on things to create a more surreal image. And I don't know if anyone knows Co Westerik. He’s an old Dutch painter. He’s great. He does these hyper close-up images of like hands grasping hands and gets really into pattern. I saw those works and I took a lot from that. And then there's something about miniatures, even in the scale of some of the works, where they become almost like these kinds of little precious things that you want to hold and take care of.

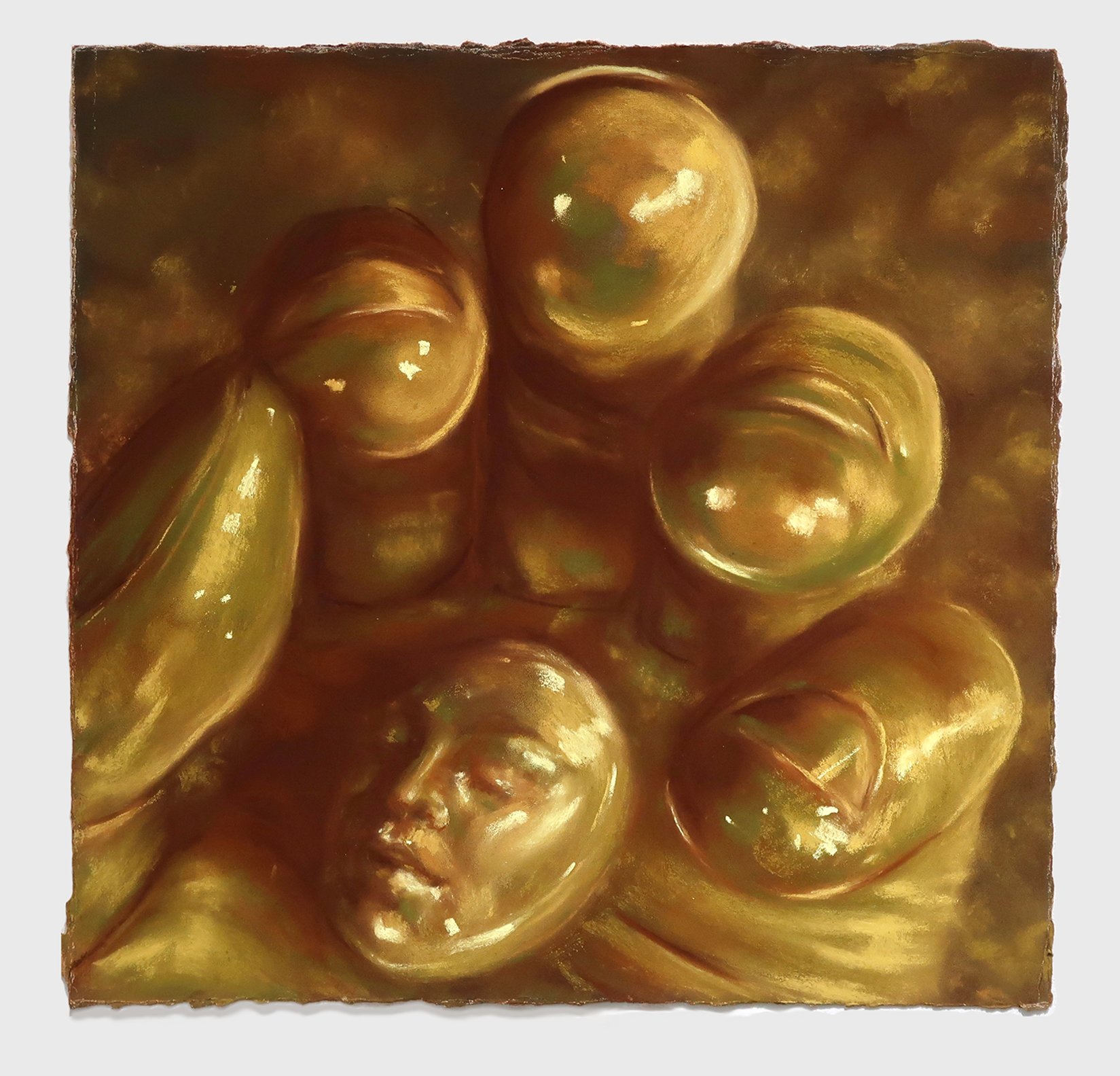

![]() Waiting for you (Part 5)

Waiting for you (Part 5)

Sophie Ruigrok, 2022

39 x 39 cm, soft pastels on sanded paper

Courtesy of the artist and Tabula Rasa Gallery

![]() Cut by grass

Cut by grass

Co Westerik, 1966

Collection Becht

@Pictoright Amsterdam

S: Yes, a few years ago, and my memory might not serve me particularly well, but I'll try my best. A book by a poet and philosopher called Susan Stewart, and the book is called On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir the Collection. She explores metaphors of the miniature and the giant as ways to look at many different aspects of culture. The book is very broad, but for her the miniature represents the interior world, like interiority, and the giant is something of the exterior world. That text had a massive influence on my visual language, and made me really think about zooming in super close on things to create a more surreal image. And I don't know if anyone knows Co Westerik. He’s an old Dutch painter. He’s great. He does these hyper close-up images of like hands grasping hands and gets really into pattern. I saw those works and I took a lot from that. And then there's something about miniatures, even in the scale of some of the works, where they become almost like these kinds of little precious things that you want to hold and take care of.

Waiting for you (Part 5)

Waiting for you (Part 5) Sophie Ruigrok, 2022

39 x 39 cm, soft pastels on sanded paper

Courtesy of the artist and Tabula Rasa Gallery

Cut by grass

Cut by grassCo Westerik, 1966

Collection Becht

@Pictoright Amsterdam

V: I'm wondering as well Sophie, if you can give us more context on your background. I'm aware that you grew up in a religious, I don't know if it's extreme religious, or like a quite a specific type of environment. But then I was really interested to know that you're actually very inspired by the spiritual or the magical. So, is there any relationship between that?

S: I grew up in a spiritual community. We had a guru, practiced meditation, had a community of people that we lived with - I grew up in ashrams. My childhood was filled with the spiritual and seeking for something greater, and the magical as well. For me, personally, as a girl I broke away from it as a belief system. But I think that kind of desire to find something more than everyday reality lingered in me quite a lot. And I think now I express that through my work. It’s definitely really influenced the way I thin.

I've always been really interested in people's religious imperatives, people's spiritual drives. So that is a big aspect of my work. I suppose what I'm interested in is the interaction between the spiritual and the everyday. They're often in parallel with one another. So often, a kind of everyday experience can have almost a spiritual feeling. Like, you know, falling in love with a person can be pretty akin to how many people describe loving God is. So that's what I'm quite interested in. So, I'm interested in the way that they kind of run parallel but also rub up against each other. Even experiences like dancing all night or like going to rave can be kind of similar to static dancing. So that is a really big undercurrent in my work. And I take a lot even from religious paintings, icon paintings. A lot of the palette that you can see in my work and the way that I emulate gold, that's taken a lot from icon work.

V: You mentioned these emotions, like falling in love, for instance, or like dancing. And in the work just behind you of the mask, there is like a very sad emotion, which is a tear. Can you tell us more about your use of the tear and the emotion it creates and also if you're interested in the actual shape of the tear itself as well on a visual level?

Relax your earth body

Sophie Ruigrok, 2022

24 x 31 cm, soft pastels on sanded paper

Courtesy of the artist and Tabula Rasa Gallery

Sophie Ruigrok, 2022

24 x 31 cm, soft pastels on sanded paper

Courtesy of the artist and Tabula Rasa Gallery

S: Yeah, so I think what Katarina was saying about depicting the unseen is quite interesting because obviously my work is relatively figurative, it can get quite surreal, but it's relatively figurative. But the tear is really interesting as a symbol because it's a symbol of something unseen - an emotion in this case - becoming material. That is - the tear is a vehicle to transform something immaterial into something material. It's almost like this bridge between the inner and outer worlds. I started wrapping my head around that idea, I became really obsessed with them. Also, on a purely aesthetic level, I love the way they look. The way that I depict them is taken from Rogier van der Weyden, who was a Renaissance painter, and he was renowned for being the master of painting grief. But I don’t think I've never really thought about the specific shape of the teardrop beyond the fact that they're beautifully spherical. And that is really fun to depict.

The mask is a symbol that's used so much throughout history and culturally. It's one of the first things that they found that we've made, and in cave paintings there are a lot of depictions of people wearing masks. They're a really powerful symbol when it comes to the idea of identity and concealing identity. Conversely, they also have the power to allow someone to actually be more themselves as it protects their anonymity. In Jungian psychoanalysis, there’s the idea of the persona, which is the idea that people have different personalities or identities that we put on depending on certain environments. Those can be incredibly useful, but also deceiving in a way. But we all do this constantly - we shift persona. With these works in particular I was thinking a lot about the idea of identity and how mask allows you to play with that.

V: Interesting, and also in the work You May Find Yourself in a Period of Deep Personal Development and Growth, the figure you are depicting has her eyes shut and her fingers in a gesture that sort of conceals her face, which brings the viewer back to the idea of mask. Your work is very figurative. But then Katarina, yours isn't and you're quite interested in an abstract language. However, I feel like as a viewer, at least myself, I feel inclined in analysing what's inside of it, or what can I find in it. Maybe all these layers, and when we were chatting, we found this thing that's trapped in the work. And I'm wondering if you can tell us if that was like a conscious decision, if maybe there was an interpretation you sought after, like looking at the work, and if you often find things trapped in your works as well?

K: I guess it was partially conscious, partially it just happened because of the way I do my paintings. I don't have any reference image and I don't do any specific things ahead of actual painting. So I basically just start off with a very thin layer of paint and then let the paint do its thing but also bringing the light back from the canvas and this way I create the sketch. While I go with it, when I actually start painting I try to see the shapes that are already there and then decide whether to keep them or not. And maybe it happened like after third or fourth layer that I started seeing the shape, trapped inside, and I started thinking of a core of an image or the heart of an image. Something very fragile but at the same time very strong. It depends on in which context you put the core. To answer your question, it was partially intentional, once I recognised that, then I decided to keep it and to go with it.

V: To clarify with the audience of what we're talking about, what seems to be trapped in this painting, is like a little egg. It seems like a little easter egg. But it's quite difficult to find, you have to really look for it.

K: I do tend to avoid any sort of associations. I know that it is only possible to some degree, but the way I do it is when I paint, if I get an association to some sort of shape, or, elements on my painting, I try to destroy it and move away from that. So, I try to find the shapes, even I cannot really determine what they are, or the associations that I have with a certain element. But here it was a bit different. Here, it is more about the exploring the nature of objects themselves, it could be basically anything, it could be a knife, a yolk, a heart, or something I don't know.

Krhqoyedro (detail),

Katarina Caserman, 2022

55 x 45 cm, oil on linen

Courtesy of the artist and Tabula Rasa Gallery

V: Maybe that is a nice thread to move into a different aspect of both of your works, the actual titling of the work. Because both of you have really interesting ways to title your work. Maybe we can start with Sophie?

S: From left to right, it is Relax Your Earth Body, Waiting for You Part 5, and You May Find Yourself in a Period of Deep Personal Development and Growth. Well, I have a few different ways that I title works, but something I do a lot of the time is I kind of save little extracts from horoscopes, or from manifestation quotes. It's often a little tongue in cheek, slightly humorous nod to contemporary ideas of spiritualism.

Installation view of Sophie Ruigrok’s and Anousha Payne work, “It is Better to be Cats than be Loved”, Tabula Rasa | London, 2022

I think in the contemporary world, everyone's so starved of spiritual experiences that people turn a lot to horoscopes as a sort of Oracle. And manifestations are almost like a form of prayer, which is quite funny when you think about how Instagramfied the whole arena is. So, I take a lot of my titles from those types of passages. And I think in a way, for me, it injects a little bit of humour into my work as well. Waiting for You is a title I’ve been using for years - it often just feels right with a particular work. I think with that piece in particular, I almost wanted it to feel like the hand had discovered this mask, like it had been waiting for the mask, which is an idea of the self.

V: And what about yourself with the titles? (Katarina)

K: I have to say that I didn't pay a lot of attention to how I title my work in the past. It was always something that came afterwards. It's something that I was forced to do just to have a title basically. I got to a point earlier this year when even I was embarrassed to tell them out loud because they were just boring. It didn’t do justice to the painting, and then I spoke with my tutor at the RCA and even she said I need to come up with better titles. A French philosopher Alain Badiou said that a new word has to be invented to be assigned to the event. And following that I was thinking of my native language, which is Slovene language.

I started coining new words, out of two or three words and I was basically inventing new words that were later on assigned to specific a painting. This wasn't out of any superficiality but it was solely because none of the preexisted words encapsulated what I want to encapsulate in the painting, so I had to come up with these new words, and I wrote them down in a way that would be easier to pronounce for a foreigner.

The main point is that you have to decode the structure of the words to understand the meaning. But at the same time, when a foreigner tries to pronounce my titles, they don't understand what it means it doesn't add anything to the painting apart from the sound of the word. Even for a Slovene person, they still need to figure out the structure first, to understand what the painting is. So, it's difficult for both sides.

Sepraznazia: A made-up word combining separacija (separation) and praznina (emptiness), together they form a noun. When one is seperated in two, the emptiness is what exist between them. However, they are not fully detached as the emptiness/void also has its own matter - Katarina

Some titles are easier to understand, some are more enigmatic. But mainly, I think what is really important to me is the structure that narrates the meaning of the word. And it's the same with the painting.

ABOUT the Artists

Katarina Caserman (b. 1996) is a London-based artist originally from Slovenia. She graduated from MA painting program at the Royal College of Art in 2022. She obtained her BA in painting at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana. In 2020 she was awarded a Ministry of Culture of Slovenia’s Scholarship for Promising Young Artists. Her work has been exhibited mainly in Slovenia and most recently in London at Des Bains. Her recent exhibitions include It is Better to be Cats than be Loved, Tabula Rasa Gallery (London, 2022). Made in Heaven, duo exhibition, Des Bains (London, 2022); Interior, Exterior, Sala Salon (London, 2021, solo); Render, Klub eMCe plac (Velenje, Solvenia, 2019); s02e02 at MGLC (Ljubljana, 2019); Fin- de-Siècle #III at Layer House Gallery (Kranj, 2019).

Sophie Ruigrok (b. 1992, London) lives and works in London (UK).

Ruigrok completed a postgraduate diploma in Drawing at the Royal Drawing School in 2019, and was selected for Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2020, exhibiting at the South London Gallery in 2021. Her first solo exhibition “today I feel relevant and alive” was held at The Sunday Painter (London, 2022). Recent exhibitions include It is Better to be Cats than be Loved, Tabula Rasa Gallery (London, 2022); Love is the Devil: Studies after Francis Bacon, Marlborough (London, 2022); A Grain of Sand, The Sunday Painter (London, 2021). Sophie has been awarded an artist’s residency in Borgo Pignano (Tuscany, Italy) in September 2022.

Tabula Rasa Gallery (London)

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Unit One, 99 East Road,

Hoxton, London

N1 6AQ

Tuesday - Saturday 12:00 - 18:00 | Sunday - Monday Closed

© 2022 Tabula Rasa Gallery